This article originally appeared in Business People magazine, and was written by Jennifer L. Boen.

Retired farmer Raymond White of rural Pierceton headed to the emergency department in August 2017 for treatment of a urinary tract infection. The ER doctor at Parkview Warsaw, a 24/7 emergency center, ordered lab work and listened to White’s heart.

“He said, ‘I’m not worried about your infection, but I am worried about your heart,’” White recalls. “It would beat at 75 (beats per minute), then drop down to the 20s. He said I needed a pacemaker.” Despite becoming a paraplegic due to a spinal cord injury 30 years ago and later developing diabetes, White had stayed as active as possible, though in recent years had noted fatigue set in more quickly. and he had frequent hospitalizations for pneumonia. Other doctors had told him the fatigue was related to pulmonary problems and sleep apnea.

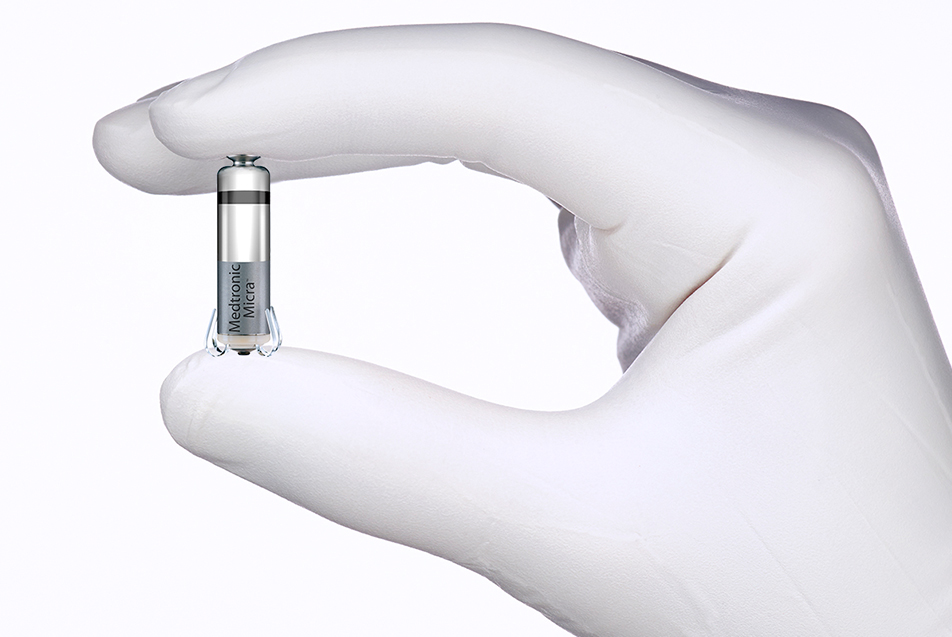

Things are different now for the 75-year-old, who says he has renewed energy and stamina – and a normal heart rate – thanks to a medical device the size of a vitamin capsule that was implanted in the lower right chamber, or ventricle, of his heart. The minimally invasive procedure was done at Parkview Heart Institute by Dr. Bradley Hardin, with Parkview Physicians Group - Cardiology. He is board certified in both internal medicine and cardiology and is also an electrophysiologist.

The Micra regulating White’s heartbeat, made by Minneapolis-based Medtronic, is the world’s smallest pacemaker and is 93 percent smaller than a traditional pacemaker, Hardin says. Parkview was the first hospital in the region to offer the Micra, which has several advantages over a traditional pacemaker that has wire leads going from the half dollar-sized generator to the ventricle or, in some cases, to more than one chamber of the heart. The traditional pacemaker requires an incision in the chest to create a tissue pocket to hold the generator.

“The weakest part of the standard pacemaker is the lead. That lead has to tolerate the force of the heart,” Hardin explains, and breakage can occur. There is also greater risk of infection at the site of the incision, and if infection occurs, it can travel from the lead into the heart, which can be life-threatening. Even for people who have a temporary external pacemaker, the leads create risk for infection.The Micra Transcatheter Pacing System, on the other hand, has no leads. It is implanted directly into the heart.

“We place it through the right or left femoral vein. We put a sheath in the vein. A catheter is preloaded with the Micra. It goes into the vena cava, across the tricuspid valve and to about the middle portion of the heart,” says Hardin, who is board certified in both internal medicine and cardiology and is also an electrophysiologist. “Little claws or tines are expanded and hooked into the tissue. It’s stable and getting good contact with the cathode,” which is the part of the system stimulating the heart. Unlike with traditional pacemakers, no lifting restrictions post-implant are imposed. Full body MRI is also allowable with Micra.

Annually, about 200,000 pacemakers are implanted in U.S. patients, according to the American College of Cardiology. The Micra is appropriate for up to 10 percent of them, and specifically, in those who need pacing only in the right ventricle, Hardin says. It is not used in people with permanent atrial fibrillation, which is abnormal rhythm in the heart’s upper chambers, or in those whose heart ejection fraction, a measurement of the blood pumping action, is normal or near normal.

White, who is married and has four children, nine grandchildren and 17 great-grands, is grateful for the new lease on life, noting, “I used to be tired and didn’t want to do much. This has really changed my life.”