This post was written by Courtney Leach, digital/social media manager, Parkview Health, following her father, Roger Hupe's, treatment at Parkview Regional Medical Center.

I write for a living. I love telling people’s stories and unearthing that sublime, harmonious combination of words, that perfect prescription of the parts of speech, that unlocks something for the reader. It’s my passion and my profession. But I was immensely humbled after countless attempts to sit down and write this particular piece. In fact, I was only able to get something down after I resigned myself to the reality that I will never be able to find words strong enough to convey my feelings. The depth of my gratitude. The enormity of my respect. I share these thoughts with you from an honest and beholden heart. One that now accepts that there are depths and dimensions to the human experience that words can’t reach. But still, I felt compelled to try.

On November 12, my husband and I attended a friend’s wedding, and my parents had our three daughters for the night. The phone rang just after midnight. My mom was on the other end. “I don’t want you to panic, but an ambulance is coming for Dad. He can’t breathe.”

After a day in the Emergency Department at Parkview Regional Medical Center (PRMC), he was moved to the Progressive unit, where we learned that his body was responding to an infection from a cat bite or scratch. My parents live on a horse farm, where people often dump their unwanted felines. With this new information, Dad concluded it must have been Hazel, who hangs out in his workshop and nips at him when he doesn’t pet her. But the exchange had been so subtle, he couldn’t pinpoint any specifics.

That Sunday night, I stayed with him in his room in the new tower at PRMC. The next morning, I kissed him on the cheek. “Just rest up, Dad,” I said on my way out the door. “I’ll see you tomorrow.” My sister was staying with him that night. A lot would happen in the next 24 hours.

Before dawn on November 15, the screen on my phone illuminated on the nightstand. There was a lengthy text message from my sister. “I’m going to start this by saying Dad is OK,” it said. “We have had a very bad night. He had a full-blown panic attack and couldn’t breathe. Then he threw up in the BiPap mask. They did an X-ray, which showed more fluid on his lungs, and moved him to the ICU. Dad, the doctor and I had a long talk, and they feel it’s best for him to go on a vent before he is in crisis and give his lungs a chance to rest. He is so tired, he’s completely on board.”

This sudden, shocking shift was the first in a series to come over the next several days. It was a Tuesday morning. I slid the door to his dark room open – the first of many times I would cross that threshold – and walked into my nightmare. He was sedated, hooked up to a crowded cart of fluids – I counted 10, maybe a dozen, that first day. My mom was pulled up beside his left ear running her thumb back and forth on his forearm. My brother was on the couch. The beeping dispensers and monitor screens that would soon become the soundtrack to our monotonous days and sleepless nights filled every inch of the space that held us.

It’s hard to be in a hospital and not think about time. The way days and people here are divided up by shifts. The fact that time with a loved one is just starting for some and painfully precarious for others. The way one second, one minute, one hour, one day here can completely alter the trajectory of the life you thought you were living; the one you thought you had some semblance of control over.

I’ve worked for Parkview for more than seven years, and during that time, I’ve had the privilege of observing exceptional members of our frontline teams. But this was not coordinated. It wasn’t scheduled or strategic. This was an unwanted collision of the compartments of my life, fusing and forcing a firsthand account I never signed up for.

That first night I stayed with Dad in the ICU, I clung to every word his nurse, Tiffany, said. I was one of a tribe of helpless, terrified travelers, and she was our guide. She had the map and the knowledge and the know-how to get us all to the other side of whatever hell we’d landed in. She adjusted the vinyl bags and vials of life-saving fluids flowing into my father, as I tucked a white sheet over the bottom of the shallow couch and pulled a flannel blanket up under my chin.

I’d had a milestone birthday the week before, 40, which felt so momentous and dripping in the dreary details people share of middle-age. And yet, on that couch, I felt like a little girl, at the foot of her hero’s bed, wishing him to wake up. To get better. To make me laugh like he always did or give me advice about anything, I didn’t care. Of course, the pendulum was always quick to swing back in the other direction, slapping me across the face with big changes lurking around unnerving corners. These were the sobering sights, sounds and scenarios of adulthood, and I hated them.

That Tuesday night, Tiffany, who’d been there when he was taken into the ICU, and who he would have again the next night, was somehow an immediate friend to me and a steadfast advocate for my dad. I was shell shocked, and, with her seasoned bedside manner, she served as an anchor. She kept explaining things to me, even when the dam cracked, and the tears came. Somehow, she sensed that I didn’t want her to acknowledge my fear. I wanted her to be the truth and the plan and the path forward. And she was all of that for me that night, and for my sister the night before and for my brother the night that followed.

Over the next six days, I experienced the same kindness from all of his nurses, technicians and respiratory therapists. We shared these intense 12-hour slices of time, where Dad’s condition would often change drastically, in either direction, rolling through the peaks and valleys of his body’s systems failing and fighting. They would learn our first names and we would learn theirs. We would pour over his complications and what, if any, progress he was making that day. And then, just like that, their shift would end and [Anna, Junice, Jana, Kyleigh, Oleksandra, Melissa] would be gone. And I’d think, surely the next nurse won’t be as amazing. And then, a new angel would land and prove me pleasantly mistaken.

My dad is a poet with profanity. He is a man who built a business from nothing in the early ‘80s with questionable health and three little kids at home. A business that, up until this hospital stay, he still went to five days a week. He gives the tightest, best bear hugs. The kind where you think your eyeballs are going to pop right out of your head. He is Papa to ten granddaughters and one grandson. He has a massive heart for animals and scrunches his nose up when he laughs, often, at his own jokes. These nurses didn’t know any of this about my dad. They had no connection to the threads and fibers of his life. But they were fighting to save him like they did.

I heard so many times, “I’m just doing my job.” But just like the inadequate “thank you” I gave to prompt that response, calling it a job simply doesn’t feel substantial enough. And thus, we arrive at my dilemma – the one that stalled this post so many times. Nothing I can say feels to scale with the compassion, skill and responsibility their work requires.

But let’s say for the sake of moving this along, that it is just a job. And each job comes with a set of tasks that have to be completed. Fine, I’m OK with that. But you didn’t have to stop by and check on him before your shift started with another patient. You didn’t have to make us laugh or celebrate his wins with us. You didn’t have to talk to him so kindly, even when he couldn’t respond. You didn’t have to wait and let me into the unit when I had to go to the bathroom at 3 a.m. You didn’t have to think about him on your drive in and your drive home, but you did. And I have the feeling you always do.

While this was my dad’s story and our story, I would be willing to put all my chips into the pot on the bet that others can relate to our experience. I know because I get to write stories like this one and this one and this one. I can turn to a tower of testimonials from families just like ours whose lives abruptly halted and were forever changed by a Parkview nurse’s presence. I know that we’re just the newest members in a club of people who pledge boundless, enormous, immeasurable, absolute appreciation to the caregivers who shed so much of themselves shift after shift.

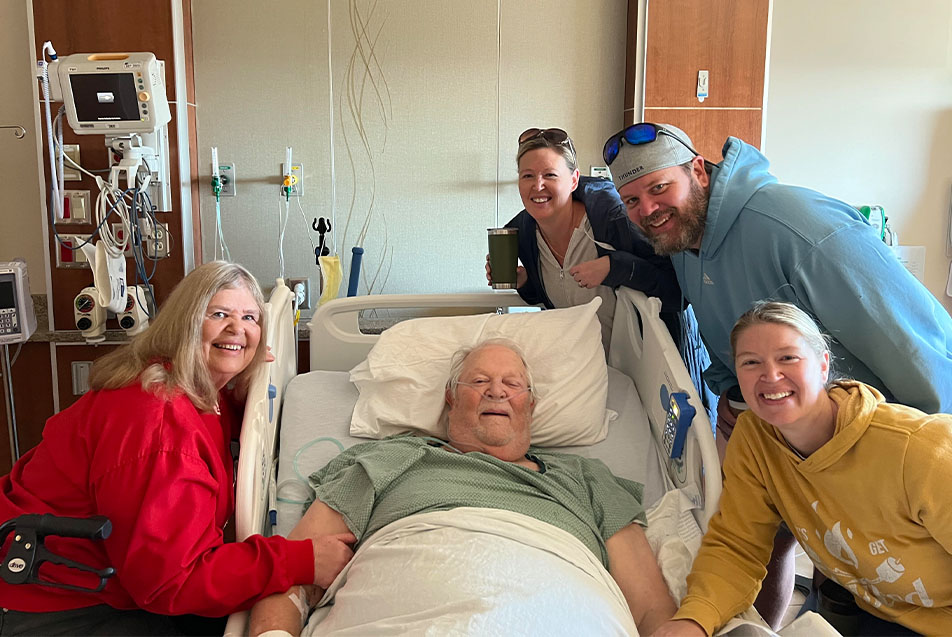

On November 18, Dad came off of the vent. On November 21, he was moved out of the ICU. On November 29, he was transferred to inpatient rehab. And on December 6, he went home, in time for Christmas and all of the traditions we won’t be taking for granted this year. The good fortune of his outcome isn’t lost on any of us for a single second.

We know that the gift of another holiday with our guy was made possible by dozens of phenomenal, selfless humans “just doing their jobs.” Round-the-clock care from respiratory therapists, intensivists, cardiologists, hospitalists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, nurse technicians, nephrologists and, of course, his nurses, most of whose names we never caught or faces were a blur through tired eyes in a dark room.

A fruit basket hardly seems sufficient in a situation like this. Which brings me back to “thank you,” a phrase more than fitting when someone holds the door for you or picks up something you dropped on the ground but seems insignificant given the gravity of their efforts. Eight tiny letters alone can never express the enormity of a second chance. Of more time together. More memories. More bear hugs.

Nothing can.

Ours is an inexhaustible well of gratitude.

If you are reading this and you play any role in patient care, please know that what you do is more than a job. It’s a lifeline, for the scared and vulnerable, both the ones in the bed and the ones who love them fiercely. Know that in the dark intersection where our paths crossed, you were our light. And consider that every thank you note you didn’t receive was likely because the person holding the pen simply couldn’t find the words that were big enough.