This post was written by Courtney Leach, social media manager, Parkview Health.

Air is infinite and imperative and powerful. It is the invisible fuel for all life. And just as we need air to exist, we need our lungs to breathe. According to Chinese Medicine, the lungs house the po, or the corporeal spirit. They are the minister within the body, advising and protecting the heart, which is the emperor. Together, the corporeal and the emperor create the heart-mind, which governs and oversees the other organs. These spirits are given during our first breath and cease with our last.

It's no surprise, then, that the way we breathe and our ability to do so is tied so intricately to the notions of the soul and self. It’s why we draw an intentional breath down to our toes when we step out into a crisp morning. Why we gently inhale the subtle sweetness of a newborn baby. Why so many sit in silence and concentrate on air coming in through the nose and out through the mouth, an intentional exercise in control and calm that can rewire a scattered mind. Being aware of the breath means tapping into a gratitude for life. For this body. This moment. It’s a gift and a gateway to come back to our senses.

As humans, we don’t necessarily have to think about breathing. It’s hard-wired into our cerebellums. And because the act is automatic, it’s incredibly alarming when something goes awry and the corporeal starts signaling distress. It’s often in these moments of suffering, of labored inhalations, that patients meet a Parkview respiratory therapist (RT).

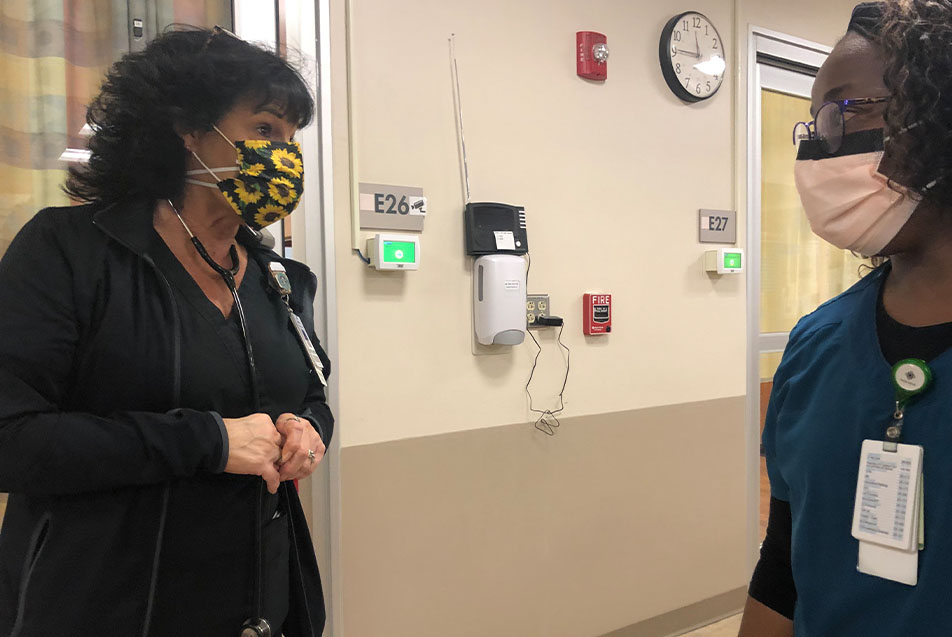

I had the extreme privilege of spending a night shift observing one of these exceptional team members, Marsha Franklin, CRT, who has just shy of 38 years of experience in respiratory care.

11 p.m.

Marsha and I had a loose plan for where we would meet, but the closer I got the more I realized I was not confident in my ability to get there, so I gave her a call. “I’ll make my way to you,” the cheerful voice on the other end said, and within minutes, she came striding down the hall – black hair, black scrubs and a perfect pop of neon pink on her feet.

Her husband was in the Ortho Hospital recovering from knee surgery. I asked how he was doing and made sure this was still a good night for me to shadow. “Oh my gosh, I rarely call in,” she said, dismissing the thought with her hand. Marsha has tremendous respect for her manager, Alisha Sparkman, RT, supervisor, Cardiopulmonary. “I told Alisha, ‘I’d be here anyway!’”

We stopped into the Cardiopulmonary offices and dropped off my things. This was my first opportunity to see some of the other team members and the space, which was decorated for Respiratory Care Week. A wall was adorned with bright balloons and streamers, there were snacks and candy everywhere (my kind of celebration) and a display of old photos shaped into an “RT.” Marsha introduced me and explained I would be following her around that night. “Get ready to walk fast,” one of the younger male RTs said.

And as soon as the warning left his lips, we were in motion, heading down to the Emergency Room to check on a patient. “I want to see if we can help this gal,” she explained. If a medical team needs to establish an alternate airway for a patient, they create a hole in the windpipe, and insert a tracheostomy tube. Once the patient is able to breathe again on their own, that tube can be removed, leaving behind an opening called a stoma. If this area isn’t properly cared for, it can result in big problems for patients, which was the case here.

Marsha assessed the wound and called the nurse over. “She’s losing air through this dressing. See how porous the tape is? I’m going to show you how we can clean this up and cover it better. Let me just grab some supplies.”

11:15 p.m.

A rapid response came over the speaker and Marsha turned to set the armful of dressing materials down. “OK, we’re going to go to that and then we’ll be back.” When a rapid response is called, a physician, lab team member, respiratory therapist and nurse are required to attend. This protocol was established to help prevent patients from going into a Code Blue.

When we arrived, care team members were gathered around the patient’s bed, talking to their loved one about medical options and, of course, their personal wishes. This individual was listed as Do Not Resuscitate (DNR). “We treat symptoms and make sure the patient is comfortable no matter what,” Marsha whispered to me outside the room. “It’s not uncommon for the family to change a DNR once the time comes. It’s hard to know what will feel right until you’re in that situation. That’s why it’s good for the family to be here and see what their loved one is experiencing, particularly near end of life.”

Once a treatment plan was decided by the response team, we knew there was no respiratory care needed for the patient, and started walking back toward the ER. “I was so naïve,” I said. “I thought the night shift might be a bit quieter.” Marsha just smiled and shook her head, never easing her pace.

We returned to the ER patient and Marsha began opening packages. She carefully cleaned the area around the stoma before placing some gauze and non-porous tape over it. Almost immediately, the patient was able to speak for longer periods of time and in clearer sentences. “Nice and easy, hon,” Marsha said. “You’re doing great. Doesn’t that feel better?”

She then made the rounds, checking in with everyone on the patient’s care team to make sure they knew of the change and would communicate it back to those who provided support to the individual outside of the hospital. To Marsha, it wasn’t just about fixing it. It was about making sure that person would have a good outcome outside of Parkview’s walls.

We stopped in to see another patient, who’d been admitted earlier that morning. After assessing the vitals and speaking with their spouse, Marsha assured them we would consult the physician and come back. At the nurse’s station, she immediately pulled up the chart and started scrolling. “The hemoglobin is so low. You can’t kill the flames with an empty fire engine,” she said. “They’ll feel better after an infusion.” This was Marsha’s favorite phrase for explaining why anemic patients aren’t getting adequate oxygen and their lungs were overcompensating. “I learned it years ago and it just makes so much sense to me!”

Word reached us that a Level 2 trauma was coming in. A stroke. We walked over toward the trauma room and Marsha explained that stroke patients are typically taken straight to CT, unless they are having trouble with their airway, in which case they would come into the trauma room and Marsha would assist. The stretcher passed us and went to the CT area, so we stood outside until someone confirmed the patient’s breathing was good and Marsha excused us.

It wasn’t even midnight yet, less than an hour into my shift with Marsha and the pace was stunning. As if reading my mind, she volunteered, “I love the ER. It’s where I work most of the time. There’s just this constant adrenaline rush.” Marsha is the Charge RT for the night shift, which means that she covers the ER, takes calls for respiratory care and floats around to help others on the team, as needed. “Night shift is great because you do and see so much. People ask if I get tired and I just don’t see how anyone could!”

While it was common to have 22 RTs on a night shift during the COVID pandemic, they currently feel fully staffed with 12. There were 11 on the night I was observing. “Working here as long as I have, almost 26 years, I have great relationships with the physicians and a lot of mutual respect.”

Marsha’s is a rich career, that started in her small hometown. During her junior year of high school, she volunteered as a candy striper at Paulding County Hospital. “My older brother and sister did it, so I did, too. When I was 18, the respiratory director offered me the opportunity to become an OJT, which means on the job training. I would clean the respiratory equipment.” At the time, Marsha was at the vocational school getting her cosmetology license. She completed that training, graduated, and went straight to Ivy Tech for her respiratory degree. “And I never looked back. Parkview hired me on May 13, 1985, and I’ve loved every minute since.”

We walked onto an elevator and Marsha hit the button, triggering a memory. “People don’t realize how far medicine has come,” she said. “I remember when I started in respiratory, there were ash trays in the breakrooms, and a woman who worked the elevator. She’d sit on a stool and punch the buttons to take you where you wanted to go. She was just the jolliest lady!”

Marsha started at Parkview Hospital Randallia at the bedside. Then, in 1990, she transitioned into the surgery space. In 1997, she moved again, over to pulmonary rehab, but inevitably, she missed the interactions with patients and returned to the bedside in the early 2000s. “The ER is my passion. There are just so many unknowns and I like that aspect. Anything could come through the door.”

While I found Marsha to be unwavering in her seasoned professional skillset, there was one area that admittedly caused the most stress for her, the Neonatal ICU (NICU). “When I first came on staff, all of the RTs had to train in the NICU right away. I worked there on and off for 25 years. And the thing about the NICU is, as soon as that baby takes a breath, those parents have hope, and they’re looking to you to save that baby. It’s powerful and intense.”

Marsha’s youngest son, Clay, has embraced that intensity. He has been an RT in Columbus, Ohio, for the past 10 years, focused on pediatrics. “He sees the babies, and just loves it,” she beamed. “We talk all the time. Sadly, they’re seeing so much RSV right now, just like us.”

When Parkview Regional Medical Center opened in 2012, Marsha was one of the first employees to make the move from Randallia. “I would come over and help stock supplies just to learn the new space. It was overwhelming.”

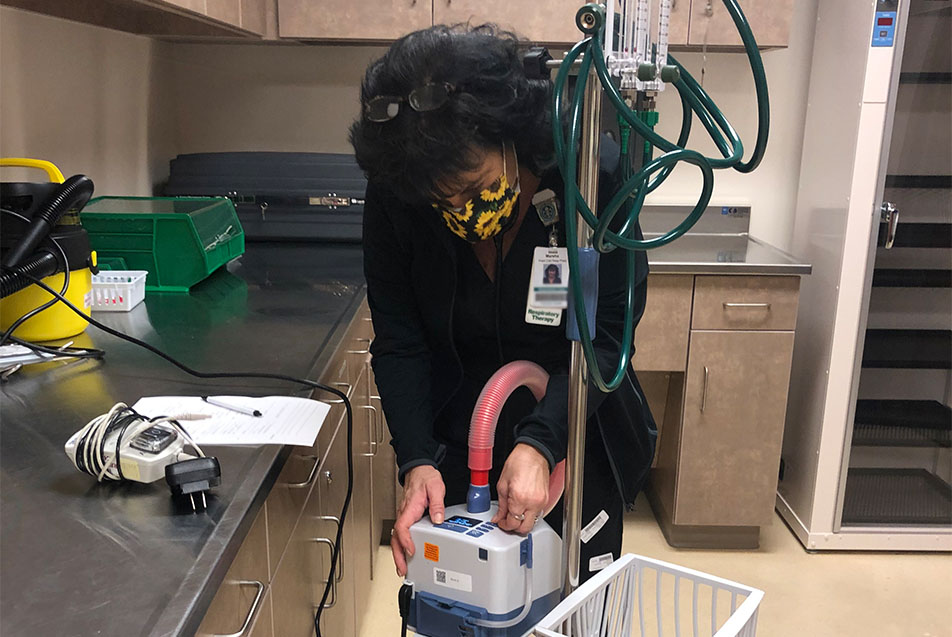

While it may have been a big job, it seems to have affirmed the veteran RT’s focus on the fundamentals. In between patients, Marsha went around and checked the equipment in the four ER rooms with ventilators. “There’s nothing worse than needing something and it isn’t ready.” Marsha’s attention to detail is as much for her as it is for the other RTs who work alongside her at night and come in during the day. Vents must always be covered, or they are considered dirty and must be cleaned.

“During the height of COVID, we would just go from room to room. For the first time ever, Parkview had an Intubation Team, which consisted of an anesthesiologist, respiratory therapist, and a nurse. We would intubate four or five people each shift,” she said. “It was crazy. And you learned the importance of having what you needed ready to go.”

12:05 a.m.

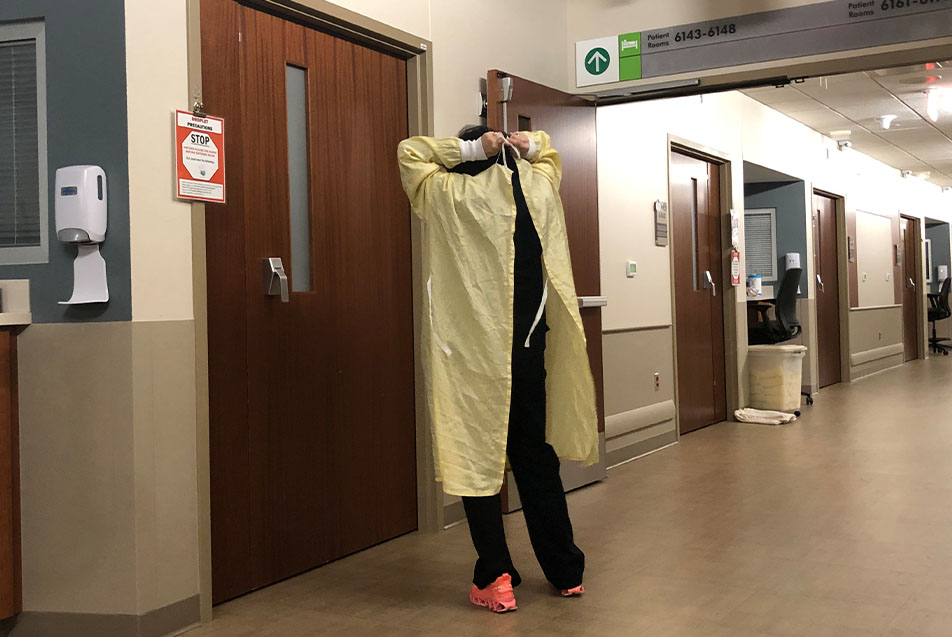

The department phone rang. Another RT was tied up and the nurse asked if Marsha could come and check on a patient. The individual had Influenza B, transmitted through droplets, so going into the room required a gown and gloves. “You just wait here, OK?” Marsha said.

Through the door, I could hear her consoling the patient. “It’s OK, pumpkin. We’re going to try and get you feeling better.” She wanted to “break things up” in the lungs, so she administered a breathing treatment and repositioned the patient in bed.

Walking after, she explained to me that RTs, and really all bedside caregivers, have a responsibility to be the voice of the patient. In my research, I read an article that explained physiologically, the only actual connection the lungs have to the rest of the body is the larynx, the voice box. The fact only affirmed for me that Marsha, a woman with such passion for ensuring her patients are heard, found the perfect field to practice in.

We walked around to check on “her people” spread out in different areas of the hospital, including the Pediatric ICU (PICU) and Medical ICU (MICU). This consisted of poking her head in and asking if they needed anything. People often talk about their “work families,” but I’ve never felt it quite as strongly as I did during my time with Marsha. She didn’t hover, but everyone knew she was close by. When she spoke of her teammates, it was like one would of their children or sibling. “We have exceptional teamwork. Everyone helps everyone do their job, and we know we have each other’s backs.” Her style has earned her the endearing nickname, “Mama Marsha,” a nod to her sweet mentorship with some of the younger staff.

In addition to a devout loyalty to her co-workers, Marsha is a stickler for protocols. She excels in the specifics, a quality that makes her the ideal Charge RT. She grabbed a supply list and we started circulating to check on the respiratory equipment stored on every floor. This includes BiPap machines and air-vos (nasal canulas). “We started taking inventory regularly during COVID so everyone knew where things were and didn’t have to go hunting them down.” Marsha also pointed out the DART carts, located in MICU, STICU, PHI and 2 North. “Only RTs can open a DART cart.” Each has supplies for setting up emergency trachs and vents.

Equipment is a vital component of respiratory care. And advances in technology are a welcome shift, though the timing isn’t always ideal. “At the start of COVID, we were actually switching to a whole new ventilator system,” Marsha recalled in between counting machines in a storage closet. “I’ll tell ya, we learned really quick. There was a lot of virtual education and, of course, hands on experience.”

The vents weren’t the only change that came during the pandemic. “We had to switch so many rooms to reverse flow in order to safely treat COVID patients,” she recalled. “Our facilities team was extraordinary during that time. I don’t know how they did it.” These rooms have remained, allowing RTs to deliver aerosol treatments to patients in three-fourths of the hospital. “This is especially helpful with the little ones.”

I’d been waiting to admit something, and this felt like the right time. “I’m embarrassed to confess; I didn’t realize how much RTs did until the pandemic. I assumed it was primarily breathing treatments.”

Marsha was so kind. “Most people thought that! I mean, I wasn’t going around talking about my job to people, so when COVID came and we started getting more recognition, I had so many people, including my oldest sons, say to me, ‘I had no idea you were doing all of that!’”

For a fully certified RT, “all of that” includes a wide breadth of responsibilities, from intubating patients to measuring lung function, resuscitation and removing life support. It is not uncommon, particularly during a pandemic surge, for an RT to be the last face a patient sees or last voice they hear.

This is one of the many reasons why Marsha and other frontline workers are thrilled to welcome families back to patient rooms following the recent lift of visitor restrictions put in place during the pandemic. “I shed so many tears during that time,” Marsha said. “When patients are here, they’re our family. I would promise to take care of them and then, if they passed, it hit me so hard. Parkview did the right thing putting those restrictions in place to keep everyone safe, but of course it was difficult, because we didn’t want anyone to feel alone.”

The COVID risk was even greater for Marsha, who takes biologics for rheumatoid arthritis, making her immunocompromised. “I’ve never been scared to walk into a patient room,” she said. “I take the proper precautions and I know what I’m doing. But COVID made me scared. It still scares me. My doctor told me, ‘If you get this, Marsha, you will not fare well.’ I will never stop wearing a mask and protecting myself.”

1:13 a.m.

We returned to make some adjustments for the patient with low hemoglobin from earlier in the shift. I stood back as Marsha attached inhalation water to the valve in the wall and the liquid came to life – bubbling noisily from its station. She switched the nasal canula and stood back to watch the monitors, like a scientist assessing a reaction. She turned to the patient’s partner. “We still have lots of tricks up our sleeves,” she said. “But this is a great start.”

Back in the hallway, she discovered a BiPap machine nestled in a corner. “I always like finding a good BiPap I can use later. We’ll just take this right back to Cardiopulmonary to clean it up.” We pushed it along like a third member of our party.

2:30 a.m.

For the first time since my arrival more than three hours ago, Marsha sat down. We were in the breakroom catching up with the other respiratory care team members, rehashing cases and events of the shift.

A group of younger RTs came in with food and Marsha’s face lit up. “These guys are so great,” she bragged, “and they’re never going to leave, right fellas?” Sean Sweeney, RT, quickly responded, “Only if you promise not to leave, Marsha.” She gave a confident shake of the head before a stroke activate came over the speaker and halted the conversation.

The patient did not need respiratory intervention, but I took our time alone to ask Marsha about the state of staffing for respiratory care professionals. “You know, these young people went through school during the pandemic, and I give them all the credit in the world for sticking with it. I tell my son all the time how proud I am of him for staying in his role, because it is such a rewarding field. But you have to be focused on patient care above anything else. That’s what it's all about.”

As a Charge RT on the night shift, Marsha is imparting years of knowledge to the next generation. When I mention that she’s quick to add, “But I’m learning from them, too. They bring the latest studies and techniques and I love that.”

I kept pace as Marsha navigated the rights and lefts that got us to the Parkview Heart Institute tower. “Any time a patient goes to the cath lab, I note that as a head’s up. We always have an RT covering this tower. It’s where we do open-heart surgeries, so we have a vent ready at all times. They don’t always need us, but we want to be available in case they do.”

In addition to checking equipment, Marsha stopped by the nurse’s station to see how many open-heart surgeries were expected the next day. Just one. Everyone seemed pleased and Marsha jotted it down on her paperwork to report back.

3:05 a.m.

“Now we’re going to see a baby,” Marsha declared. “We have a stridor, which is often a sign of croup.” From the moment she walked into the room, Marsa instinctively recognized she was treating both the parent and the patient. She assured the mother, nervous and questioning, that she’d made the right call bringing her 16-month-old in. As she held the mask to the little one’s face, she stroked the infant’s hairline, a gentle, compassionate gesture amid the fog of medicinal intervention. It was a familiar motion for the grandmother of five, coming naturally and in perfect time. The ER was full that night, but she was entirely present for this tired pair.

3:25 a.m.

We went a few rooms down so Marsha could administer a breathing exercise to a patient who had a bronchoscopy earlier in the week. She was gauging how much air the patient was taking in. Not satisfied with his result, she found a computer at the nurse’s station outside of the room and pulled up the chart, clicking and scrolling and nodding. “Each patient is a puzzle, and we’re just collecting and putting pieces together until we figure it out.”

3:45 a.m.

Within minutes, two stroke patients arrived in the ER. “Some nights are just like this,” she explained. “That’s why I’m so grateful for our teamwork. Our managers are working managers. They will come out and help if we need them, and I assure you, it’s not like that everywhere. But it’s always been like that at Parkview.”

4 a.m.

After a brisk adventure tracking down a patient who’d been moved, Marsha entered a dark room to administer another breathing treatment. Her face aglow in the electric wash of the computer screen, she gently prompted the drowsy patient to confirm information so she could begin. The television muffled in the background, Marsha worked to make sure the individual was warm and settled in for the night. “Now give me a strong cough and move that medicine down. Beautiful. Get some sleep, honey.” In and out, like a pharmaceutic Tooth Fairy, always cognizant of the sensitivity that comes with these pre-dawn rouses.

4:30 a.m.

Back in the breakroom, I asked Marsha if it was OK to revisit those difficult days of the pandemic. “I remember the Ebola scare, H1N1 and swine flu, but I’d never seen anything like COVID. In the beginning, no one was getting better. We didn’t know if we’d been exposed or just how bad it was going to get. Vents weren’t working. It scared a lot of people off because the point of intubation is a very transmissible moment with a virus.

“Mentally, it was terrible. I lost 25 pounds. I couldn’t eat. My love of the job kept me coming back, but the fear was so overwhelming at times. It’s hard for people to understand, but those first two waves were terrifying. Then Delta came along, and it started taking young people, and that was really scary. We’d have a 40-year-old, seemingly healthy individual with no underlying conditions, and we couldn’t save them.

“It brought the respiratory team so close. We would stand in the parking lot for 30 minutes after a shift and just talk. No one else could understand what we were going through. I didn’t see my son, Clay, for months, but we would have long conversations about what was going on. I divided my house into two sections and wouldn’t let anyone get in my car. I didn’t see my kids for Mother’s Day. We had Christmas in a barn, and everyone had to wear masks and stay in separate corners.

“It was such a sad time for me. I’d leave the hospital and just cry the whole way home, knowing how many I’d lost that day and how many those coming in for the next shift would lose. I went to school to help people. Not to tell them everything would be OK, knowing it might not be. It was hard and changed everything for me. It was impossible not to take the fear home. Some RTs couldn’t get dentist appointments because no one wanted us in their offices. We didn’t want to hurt anyone, either.”

In traditional Chinese medicine, the lungs are the organ most connected to grief. They interact with the outside world, breathing it in and letting it go. When we do not let go of our grief, it’s almost as if it can fester in our lungs.

Which is why we need hope.

“The arrival of the vaccine was pivotal. That’s when I first saw the light at the end of the tunnel. In fact, when my leader asked me if I wanted to be among the first in the state to receive it, I never hesitated. I was the second person in Indiana to get the COVID vaccine. I’ve gotten all my boosters since. I wanted to do everything I could to stay with my team on the frontline. I could never leave them. But even with this protection, nothing has really changed. I can still get COVID, and I can still die from COVID. It still scares me after everything I’ve seen. I will never stop being careful.”

There’s a small amount of air, known as residual volume, that always stays inside our lungs. This prevents the smaller airways and alveoli from collapsing and keeps them open just enough so that the next breath comes easier. Pain, in some ways, is comparable. It’s a residual reminder of where we’ve been and how it changed us.

When I asked how the pandemic altered Marsha’s life, she shared a renewed sense of purpose. “Before the pandemic, I was honestly thinking of quitting my job. Just questioning things, but I’m not anymore. I can honestly say that I no longer take things for granted. I lived here during the height of COVID, and I know that no day is guaranteed. I treasure my family time so much more. Since COVID, I haven’t been able to relax in shared spaces, like hotels. Finally, my husband said, ‘Let’s try something different.’ We bought a motor home a year ago and started camping. It’s been so great. Other therapists camp as well, and we meet up. I can actually relax.

“Once we started to see people surviving this thing, it turned around for me. But the thing people need to know is that many who had the virus and were so sick, walked away with severe deficits to their health. We see patients over and over again who are struggling from severe lung damage. It has altered their lives.” Just as it has altered the lives of those who helped make another day possible for them.

5:30 a.m.

My time with the “backbone of the nightshift” was coming to an end. She had paperwork to tackle, and I had kids to get off to school. She graciously offered to walk me back to the place by the bridge where we’d met hours ago. A spot from where I knew how to get home.

I asked her one last time if she ever thought of stepping away. Of doing a little more camping and taking fewer, slower steps. “I love my job,” she said, confirming that Mama Marsha has no plans of retiring any time soon. The corporeal spirit is safe for years to come.

I walked out into the parking lot, met by a dark-washed denim sky dotted with lingering constellations and the promise of dawn not far off. I stopped my feet, placed my hand over my heart and took a long, intentional breath through my nose until I felt my chest expand beneath my palm. I allowed gratitude to wash away any symptoms of exhaustion and flood in. I was aware of my body. The moment. The gift of my time with Marsha. And for the first time in seven hours, I took short, slow steps all the way to my car.