Enjoy this post by Courtney Leach, social media manager, Parkview Health.

From a very young age, we’re taught that fire demands respect. In many ways, it’s forbidden; meant to be admired only from afar. Few things that beautiful have such a venomous bite, and getting too close carries unthinkable consequences. Despite a lifetime of lessons and intentional avoidance, on a nearly cloudless Saturday at the end of September, I found myself sitting shoulder to shoulder with 11 strangers in a flashover chamber, observing the hypnotic habits of one of Mother Nature’s most powerful elements.

I was invited by Mark O’Shaughnessy, MD, Parkview Heart Institute, to participate in Fire Ops 101, an event hosted by the Fort Wayne Professional Firefighters union, where state and city officials, business owners, educators and healthcare professionals get to experience life as a firefighter for a day. Dr. O’Shaughnessy is a close friend of the FWFD, and, though he’d completed Fire Ops once before, he planned to put the helmet on again this year. He assured me it would be an unforgettable experience, and after some hesitation, I eventually concluded that, when Dr. O’Shaughnessy encourages you to do something, you should probably take his advice.

Friday night before the event, we gathered at the FWFD union hall on Broadway. Our hosts had provided an impressive buffet of dinner options, and there was a buzz of tentative enthusiasm running through the conversations.

We took our seats and Dr. O’Shaughnessy joined Jeremy Bush, President, Fort Wayne Professional Firefighters Local 124, and Philip J. Wyss, PAC Chairman, Fort Wayne Professional Firefighters PAC, at the front of the room. With his signature bow tie undone around his neck, the physician shared that the most common cause of on-duty deaths for first responders is cardiovascular incidents.

“One year ago yesterday, Captain Eric Balliet, a 19-year-veteran, lost his life to a cardiovascular episode,” Dr. O’Shaughnessy said, pointing to a framed portrait on the ledge behind him. “I’ve been working with the fire department for almost five years, and last year we lost two people. That’s too many.”

While I knew Dr. O’Shaughnessy worked with the FWFD, this was my formal introduction to the unyielding passion he has for these public servants. He began looking into the department’s wellness and screening process six years ago, after a New Haven firefighter lost his life to a cardiovascular episode.

“All firefighters are required to have a treadmill screening test. But this really just tells us their O2 capacity. A coronary artery calcium scan (HeartSmart) can show us if they have any calcified or hardened plaque buildup that should be cause for concern. This can be an incredibly effective warning sign. If we see something on the HeartSmart, which costs just $50 per person, then we can order a treadmill, which costs $500 per person. We’re saving the department money and, hopefully, saving more lives.”

Dr. O’Shaughnessy later told me that he could also leverage input from the required Work Performance Evaluation crew members go through to determine O2 capacity, as opposed to the treadmill exam. To date, Dr. O’Shaughnessy has screened more than 1,000 public servicemen and women. In fact, most of them have his cell phone number.

“What people need to understand,” he shared, “and you’ll experience this tomorrow, is that firefighters are under some serious physiological stress, including anaerobic, aerobic and strength demands, as well as elevated cortisol, thermal extremes, hydration, heavy gear and psychological stress.”

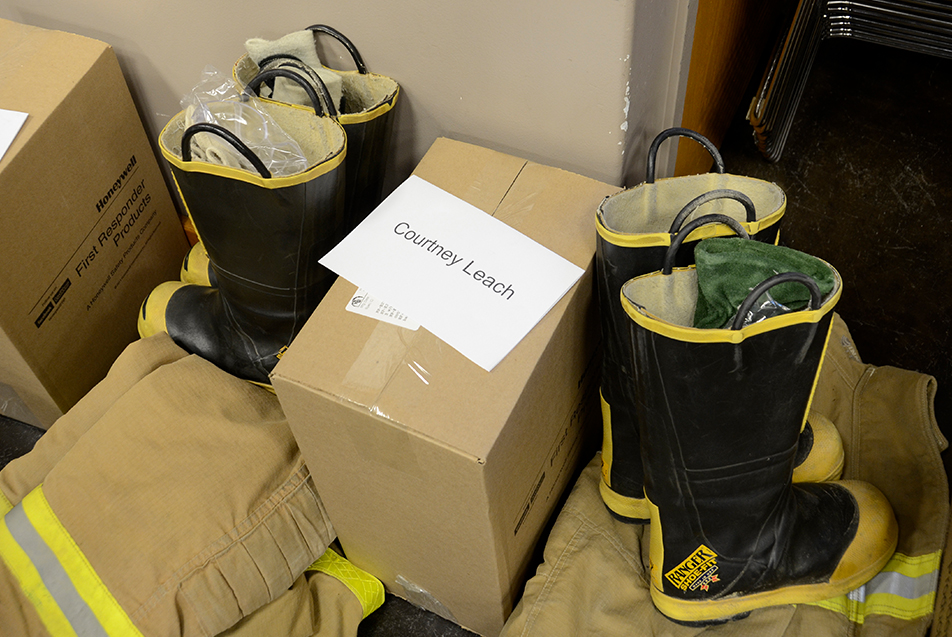

The doctor handed the floor over to Jeremy and Philip, who thanked us for our participation and ran through an overview of the next day’s activities. We were then dismissed to try on gear. Along the back wall, a row of neatly stacked piles of thick camel-colored pants and jackets, gloves and rubber boots awaited. Next to the clothing, on top of a sealed box, sat a piece of paper with our name.

Private Amanda Dreher spotted me half-heartedly eyeing my pile, and came over. “You ready for this?” she asked, and I wasn’t sure if she was just referring to trying on the gear. At her advisement, I pulled the pants on first, then the suspenders. Next, with my hand on her shoulder, I stepped into the boots. These, I could tell, would be the thorn in my amateur side. Next came the protective hood. I pulled on the jacket and Velcroed the collar shut.

Amanda leaned over and broke the seal on the box. She pulled out a helmet, still wrapped in protective plastic. “This was always a big deal,” she smirked, “when we finally got our helmets.” She reached over and placed it on top of my head and I felt the weight of it, in all of the ways one feels weight.

“OK,” I said, “Now I have some girl questions,”

“Great,” she welcomed.

“Will my hair fit under my helmet if I wear it in a high ponytail?”

“You’ll have to play around with that throughout the day.”

“What should I wear under all this?”

“The less, the better. You’re going to sweat.”

“My boots are too big.”

“Wear two pairs of socks.”

I thanked her for imparting her wisdom, and she wished me her best. Just as we were getting ready to go our separate ways, I mentioned that my only hesitation was the obstacle course, which I’d heard involved navigating tight, enclosed spaces – not ideal for a gal with a paralyzing case of claustrophobia, like me.

“That’s OK,” Amanda said. “Take that fear with you into the experience and acknowledge that it’s there. It’s just like yoga, if you do yoga. You step onto the mat, you take a few deep breaths and you acknowledge whatever stress and tension you’re bringing onto the mat with you that day. Same concept.”

Heading out of Downtown that evening, traffic was slow. Construction was everywhere, and so were my thoughts. I heard the howl of sirens to my right and within seconds a fire engine passed by, a few intersections ahead. I smirked at the symbolism, and the light turned green.

The next morning, I left my family, still deep in their dreams, and dim suburban neighborhood. A rising rainbow sky greeted me to the east as I easily navigated the sleepy Downtown roads. When I arrived back at the union hall, the Fire Ops 101 participants and a healthy sea of firefighters filled the space. Card tables were crowded with scrambled eggs, sausage patties, warm biscuits and a giant pot of homemade sausage gravy, the officer with the culinary touch, retired Captain Randy Zion, still lingering over the stove in the hall’s kitchen. I assembled a generous plate and indulged in a second cup of coffee.

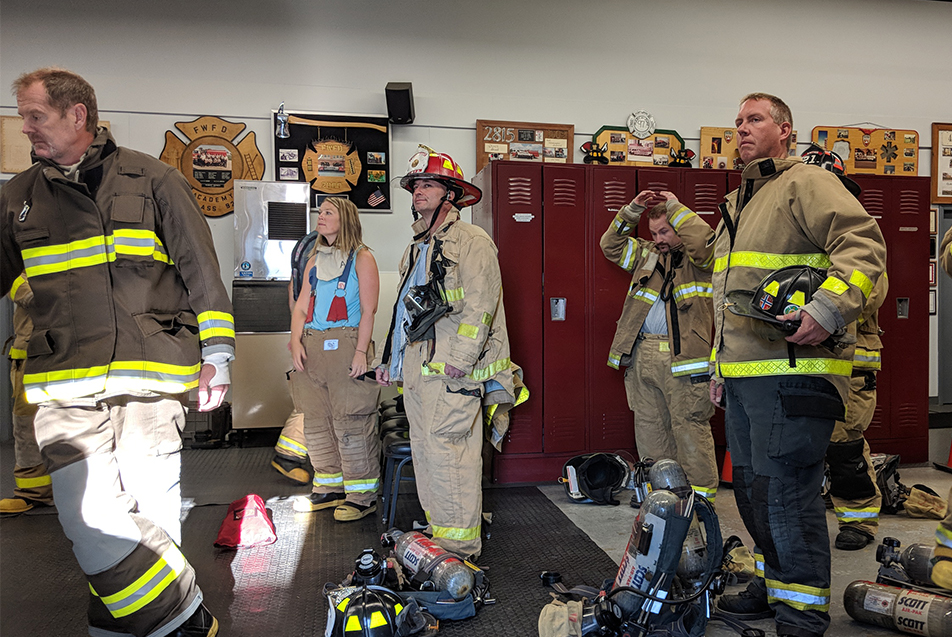

As I savored the subtle bite of the spices on my plate, Jeremy and Philip returned to their spot at the front of the room, where I’d left them less than 12 hours before. They divided us into three groups. Each group would have at least two designated handlers (firefighters) and four Fire Ops participants. My group, led by Lieutenant Chad Girardot, Private Jason Fleming and Private Brandon Spreng, included myself, Dr. O’Shaughnessy, Rob Robison, the vice principal at Wayne High School, and Stephen Reuille, with Petroleum Traders.

“Now, remember, communication is key. Talk and look out for each other. We’re a group,” Philip said.

“Alright!” Jeremy took over, “When you hear the alarm sound, you’re going to have 1:45 to get your gear on and get to your truck.”

Minutes later, clutching Brandon’s shoulder, I was unsteadily burrowing my feet down into my oversized rubber boots. In the order I was taught, I layered on the heavy gear – suspenders, hood, jacket, helmet – and grabbed my other belongings. I could barely see out from under my brim. My hands were impossibly full, balancing my camera and backpack and oxygen mask. I was walking like a toddler in her father’s dress shoes. It seemed humility was the course they served up just after breakfast around here.

I tossed my accessories up into the truck, grabbed the handles and heaved my body, weighted by the insulated attire, up onto the shiny metallic steps. After some jostling, I finally positioned myself in the narrow jump seat and clicked the seatbelt. Through the open window, the Downtown landmarks started passing by as the long fire engine maneuvered through the grid of one way options. When we turned onto Dwenger Avenue, the sirens and lights started wailing. A couple walking by thanked me and Stephen for our service. We waved and looked at each other like guilty children.

We all piled out of the firetrucks and reunited with our groups. The day would bring five rotations, each designed to offer a different hands-on experience. Our first stop was an extrication using the “Jaws of Life”. Turns out, just as there’s a step-by-step process for assembling a car, there’s also a process for taking one apart to free a trapped or pinned accident victim.

We began by placing wooden wedges under the tires to stabilize the vehicle and silence the suspension. (It can be difficult to work on a moving target.) Next, we broke some glass. I was handed a small tool with a tiny spike on the spine. As instructed, I tapped the spike against the bottom corner of the back window. Nothing. I tapped again. It shattered into an intricate web of fractures. I used my gloved hands to clear all of the glass out of the frame. My reference to the Carrie Underwood, “Before he cheats” video was entirely lost on my all-male partners.

After each of us had a turn clearing a window, they brought out the heavy machinery. I watched each of the gentlemen step up and take a turn with the robotic claw. Slowly the tension created by the opening limbs would grow, the inner workings of the door would moan and pop and stretch, until Bam! Something would fall away from the car and the operator would exhale.

When it was my turn, we were on the last door of the exercise, and there wasn’t much left to disassemble. I grabbed the top handle of the machine and felt my entire shoulder fall toward the earth. A standard model Jaws of LIfe machine weighs 48.1 pounds. Add to that the awkward angles and length of time it’s being utilized and an extrication can drain a team member pretty quickly. Within seconds, I felt sweat rolling down my spine and pooling in my protective goggles.

.jpg)

The hydraulic machine generated a frightening force of energy between me, the firefighter helping me hold it, the car and the car door, and as it expanded and I heard the pops and strains, I was keenly aware of my position in relation to all of the potential moving parts. It would take a split second to get pinned myself, in the process of trying to save someone else. My situation was unique, in that someone was there to reposition me or take the hefty Jaws off my hands. But holding that kind of power makes you realize the risks and the demands at play for rescuers.

“Now, imagine what that sounds like to the person trapped in the car,” Jason said. “The noises, the glass. That’s why we cover them with a blanket and talk them through the process. Here’s what you can expect next. Here’s why we’re doing it. They’re trapped, their children might be trapped, and they want out. Our job is to get them out, but also keep them calm.”

A voice came over the radios indicating it was time to rotate. We would be treating a trauma patient. I found a few familiar faces at this stop, Matt Stieber and Adam Fischer with the Parkview Mobile Simulation Team. We used their sophisticated manikin to perform chest compressions and provide air via a manual resuscitation bag.

When I was a little girl, firefighters were the men in black coats who loved Dalmatians and ran into burning buildings with ladders tucked under their arms. But the world is a little scarier when you grow up, and now I know that our firefighters aren’t just running into towering flames. They’re running in to save people from heart attacks and gunshot wounds and drug overdoses. They are the first set of boots on the scene of someone’s worst day.

“Anything you can do is better than nothing,” Jason said, after demonstrating the procedure for an unconscious patient. In any given firehouse, you’ll find team members with varying degrees of EMS accreditations. There are EMTs with basic life-saving skills, Advanced EMTs, who can administer IVs and place airway devices, and paramedics, who have the most medical training and can administer medications as well as facilitate advanced life support techniques.

“Whatever we do in that first 2-3 minutes will be the most important thing we ever do for that person’s life,” Chad said. “And if you think it doesn’t matter, then you haven’t heard the story of the jellyfish. A boy walks down the beach after a storm, and the beach is covered in jellyfish, so he starts picking them up and tossing them back into the ocean. His father tells him, he’ll never make a difference, he’ll never save them all. ‘But I can save this one,’ he says, tossing it back in, ‘and this one, and this one.’”

.jpg)

Moved by the fable, I volunteered to try compressions first. I dropped to my knees and laced my fingers together, one hand on top of the other. I leaned over my forearms and started pushing down on the manikin’s chest with all of my weight. The gauges on the Sim Lab’s computer were barely registering my efforts. Soon, I was sweating. Again. After just one minute, I was gassed. I hadn’t done anything to save this “victim’s” life and I felt depleted and discouraged. The others in my group had far more success, delivering aggressive, heart-jolting pumps.

I repeated my disappointing performance with the resuscitation bag. The technique, which looked so simple, actually requires strong hands for sealing the mask around the patient’s face to deliver the oxygen. My bicep shook and my thumb began cramping as I strained to keep the necessary apparatus in place. I sat on my heels in defeat.

“Let’s go climb some ladders!” Chad said from somewhere over my shoulder.

A ladder is the ultimate rescuer’s accessory. It’s big and attention-grabbing and can provide access to the direst of situations. As climbs go, we were treated to a special opportunity. Ray Easterly with New Haven/Northeast Fire Department had graciously volunteered to bring a “tiller” truck to the event, and an email had circulated earlier in the week promising a free dinner to anyone who could climb the ladder on the truck all the way to the top, without needing rescued. The proposition felt different now, standing at the base of the 90-foot obstacle. Nevertheless, I raised my hand.

“You’re going to climb that?” Dr. O’Shaughnessy asked, his eyebrows stretching toward the base of his hairline. Everyone had their things out there that day. For Dr. O’Shaughnessy, it was heights. He didn’t care for them. Never had. But bravery had a way of showing up on that sunny Saturday. “Give me your camera,” he motioned. “I’ll go up in the cherry picker on the other truck and take your picture at the top.”

I knew that was a big deal for him. The ladder on the other fire engine reached 100 feet up toward the heavens. I knew that was him proving something to himself and showing up for me as well. I handed him the camera and walked over to the tiller.

I discarded all the gear they’d let me and hoisted myself onto the back of the truck. To my surprise, I wasn’t going to be tethered. Rather, I was told that, if I needed a break, I should stop, loop the strap I was wearing around the nearest rung and take the time I needed. Other than that, it was just me, my spotter and 90 feet of white steel.

I wrapped my hands around the side, swallowed hard and stepped onto the first rung. Each step was slightly different from the last. Some rungs had two bars, some had one. Sometimes the side rails were single, others they were double. My knuckles were white as a wedding lily as I gripped tightly, being careful to wedge my oversized boots securely onto each step.

Rung by rung, grip by grip, I made it to the top, the once sturdy ladder now swaying and narrowed beneath me. I heard a voice yell my name and turned to wave at my favorite cardiologist in the cherry picker across the sky from me. I smiled for the camera but didn’t care to linger. Gingerly, timidly, I began my snail-like descent back to the safety below. Once grounded, standing next to the tiller truck, looking up toward the sky, it was hard to believe my body had been a sizable dot on the brilliant blue canvas just seconds ago. I felt a surge of belated adrenaline.

Our third rotation was all about the waterworks. Captain Tim Bail was ready to put on his one-man show about commanding the nozzle and making the spray from the hose come down on the flames “like an August rainstorm”. With dramatic delivery, Tim tapped into his favorite 80s rock gods as he demonstrated how to nestle the forceful fire hose in the pocket of your hip and lean back as it unleashes a powerful downpour. “I don’t want to control a fire,” he said, fist clenched by his face. “I want to kill it.”

Before he turned us over to our handlers for the drill, he left us with this, “There’s never no one left to save until the Fort Wayne Fire Department says there’s no one left to save, OK? Every day I walk by a sign in the firehouse that says, ‘I give my life to save a life’. I have a little girl. And I would like to think that, if we had a fire, she would find the one, tiny, safe space in our home, and that someone would come looking for her. Every child in this city deserves that.”

We geared up, this time with our oxygen masks and hoods, and took our places around the hose. The first two participants, Rob and Dr. O’Shaughnessy, carried it into the building and up the first flight of stairs. Stephen and I were the second wave of responders. We were there to help advance the hose and navigate any points of resistance. When I received my cue, I bent down and grabbed the yellow plastic – it was like holding onto a tornado in a bottle – and entered the building.

I stood at the base of the stairwell in the shadowy, stripped down structure and watched the water run down onto our heads from the floor above. The most recent spray now trickled over the concrete steps, creating the illusion of a kitchen window after a summer shower. Like an August rainstorm, I suppose. It was almost possible, in this haunting light, through the lens of my mask, to imagine being the one who goes in when everyone else has already come out. Almost.

Chad took Stephen and I to the third floor and explained how the team would go about searching for victims in a fire scenario. The third floor was mostly dark, with sunlight whispering around the boarded windows. Stephen went left and I went right, combing the room on all fours. Chad told us to use our hand closest to the wall as our guide and our other hand to discover. “What’s in front of you?” he asked. “What does that feel like? Call it out. Let your partner know. Communicate.”

I found a chair and Stephen found the base of a bed. I found a crib and stood to reach down and make sure nothing was in it. We found a bathtub and dressers, but no victim “Stephen, you said you felt a bed,” Chad said. “Did it feel like a certain type of bed?” We crawled back toward the entry to the room to relocate the mattress. My mask was tight and the air felt thick. It was like breathing through a straw in the desert. We arrived back at the bedframe and used our hands to gather more clues. “What type of bed does this feel like?” Chad asked again. “It feels like a … a bunk bed,” Stephen answered, and my heart sank.

Even though it was a teaching scenario, even though I knew we were searching for a pretend victim made of fabric and stuffing, the thought that we failed to save someone made my stomach turn and my eyes shut in shame. No one was on the top bunk. In fact, there was no manikin on the third floor at all, but the introduction to such responsibility will never leave me.

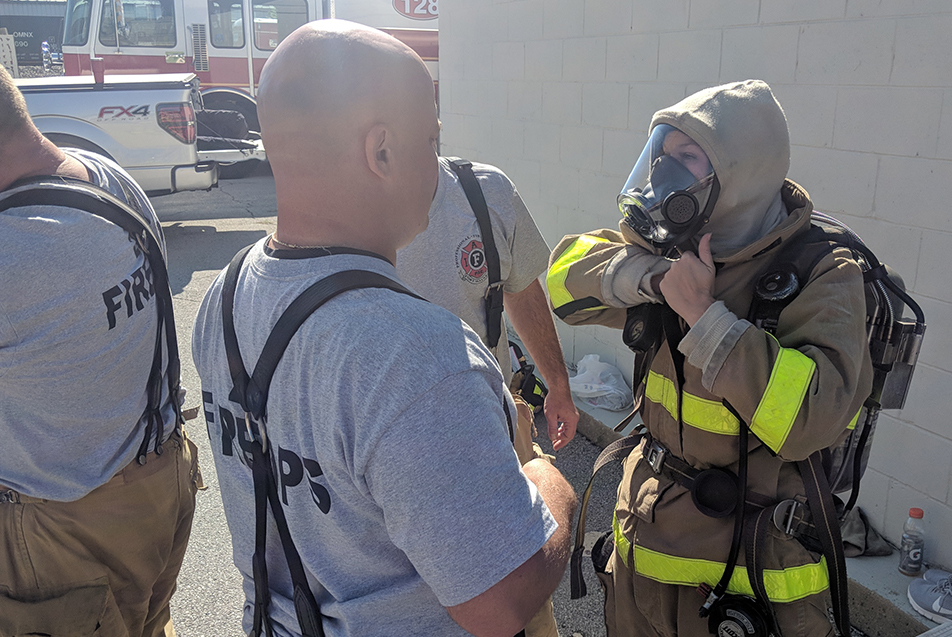

It was time for the fourth stop of the day; the one I’d been dreading for a month. The ironically named, “confidence course”. They first walked us through with the lights on, explaining the real life obstacles the simulations were designed to represent. These could be anything from tricky crawl spaces to unstable, soft floors. This was also the first time all day we utilized our oxygen tanks. “Being in a fire is like being underwater,” Jason said. “You don’t take your oxygen off, but it takes some getting used to.”

“Right,” Chad added, “You’re asking your body to go against its nature.”

Around that time, Philip came over with a proposition. He was looking for someone to wear an action camera through the course. This would mean they could leave the lights on for their run. Without thinking, I volunteered. This was the out I’d been hoping for since I heard the terms “darkness” and “entanglement”. As the others in the group chatted, I came back around to the proposal. “Actually, no,” I said, “I think I should go through in the dark.” I caught a glimpse of Chad nodding in my peripheral.

I pulled the oxygen mask over my face and felt the suction pull at my skin as my handlers carefully tightened the straps, ensuring the proper seal. We tucked the hood up over my hair and the back of the mask. Then my helmet. For someone who struggles with feeling confined, this process resembled being vacuumed into a fish bowl. Chad helped me slide my arms into the straps of my oxygen tank and grabbed the black adaptor. He twisted and locked it into my mouthpiece.

“Now take a breath,” he instructed.

I did, and the life-giving air began rhythmically releasing into my mask. My own exaggerated inhalations and the robotic respirations of the apparatus were amplified in my ears. From behind the plastic, I felt like an observer, the activity of the day happening around, but not to me. My thoughts were growing mildly hysterical, but manageable, as I felt a light dew form around the seal of my face mask. “You ready?” Chad asked. Time to go. Dr. O’Shaughnessy gave me a thumbs up. They opened the door, I indicated I’d be going from right to left, and just like that, everything was dark. While I’m certain there were other volunteers in the building, it felt like there were only three of us: me, Chad and my fear.

My right hand clumsily followed the wall, while I rammed my helmet and oxygen tank into the tops and sides of the wooden course. At one point, I was frantically tossing foam blocks, trying to dig my way into what I thought was a passageway, but was really a particle board wall. Everything in me was heightened.

Always, there was a voice to serve as my lighthouse, “What is your guiding hand touching?” “What’s in front of you?” I’d come back to my memory of the course. It was the ramp. It was the attic boards. I came to a tight hole, put one arm over my head, recalling their instruction to “swim” through. My breathing felt wild and desperate. The gear was indescribably hot. I was more exhausted than I’d ever been.

I came to the dangling wires and sat back on my boots to force my escaped feet down into them and collect myself. I thought of Amanda, and acknowledged my anxiety. More than anything, I wanted to get through this without losing control. I wanted to dominate my insecurities and diminish the doubts I had been entertaining for days. I wanted to shake hands with a stronger version of myself. I angled my body sideways and slid the oxygen tank along the floor, shoving the wires, and my panic, away.

Toward the very end, when he asked if I wanted to go through the tunnel – an obstacle only a few of the others had completed – I don’t think Chad was trying to access an untapped competitive edge sleeping deep inside of me. I think it was his way of holding a mirror up to my perception of my limitations and offering me a sledgehammer. It was a gift; an invitation to prove to myself that I was braver than the monsters in my head, and I was fiercer than my fear of the unknown and I was mentally tougher than any small space or box that someone might put me in.

I took a deep breath, clenched my face, and army crawled through the smooth tunnel, salty sweat streaming down over my face. I heard my oxygen tank release a gasp of air, then quickly another. I reached up, pulled myself to the edge, on the other side, and just as I felt the tears piercing the backs of my eyelids, I heard someone say, “Awesome! Now do it again, we want to get a picture!”

I’d love to say that when I walked back into the brilliant sunlight my group erupted in applause and crowded around to hoist me up on their proud, proud shoulders. But, while there were some words of praise, the accomplishment felt surprisingly intimate. I was the only person who knew how tough those last few minutes had been for me. And I was the only one who could grant myself permission to celebrate the triumph for what it was. But I also know, with absolute confidence, that sweet reward was a manifestation of the voices I heard in that room, the humbling gift of their belief in me and the trust I had in them within those walls. Four exercises in, I was beginning to feel the spirit of the firefighters.

There was only one thing left to do: Face the fire

The world of firefighting is changing. Less people are going into trades, which alters the pool of participants. And where organic materials like cotton and wood once reigned, our homes are now filled with petroleum accessories, fuel for any spark. The demands are accelerating.

Unfortunately, firefighters learn through tragedy, and after a flashover fire at the old Athletic Club in downtown Indianapolis claimed the lives of two firefighters in 1992, the FWFD built a flashover chamber as a tool for understanding the current nature of fires in our evolving environments.

And now we were going to sit in it.

To fully picture this scenario, you have to understand something very important about the oxygen tanks. Each tank features a sensor, designed to alert team members if another firefighter is trapped or becomes immobile. After so many seconds without movement, the tank will begin to beep and a red light will flash. If the crew member still doesn’t move, the alarm and flash increases in intensity until, finally, it has to be reset. You can appease the sensor and buy more time, we learned, by shaking or swaying your body just enough to please it.

Our handlers worked wildly between us, adjusting masks and checking oxygen tanks like a kindergarten teacher manipulating costumes backstage before the big class play. We left them outside and filed into the chamber, filling two benches running perpendicular down the space. Captain Jim Noll lit the fire at the front of the room.

The flames were small at first. Smoke began lazily filling the top of the chamber. Through the haze I could see red lights sporadically pulsing on the chests of participants across from me. Someone would point to them, and they’d shimmy to silence the alarm. We had to be careful not to touch each other; our gear is designed to trap heat, and pressing on the material could transfer that heat to the skin.

As the neon hues of blue and purple and orange began to crawl up the back wall of the chamber, no one turned from the commanding display. It was mesmerizing. Every few minutes, Jim would say, “rotate,” and the two participants closest to the flames would drop down on their hands and knees and crawl to the back of the lines. He’d tell them to open the door to the chamber, and the air would taunt the flames to surge and spread. Then they would shut it, and the display would quiet, and the smoke would fill the space between us.

Jim would explain the influence of fuel and oxygen, pausing every so often to spray the encroaching inferno, like a lion tamer with a whip in his hand. In my imagination, he scolded, “Back! Get back!”. The hose was a serpent’s tongue, lashing out and striking the bold heat. The brim of dark smoke over our heads gave the illusion of sitting on the floor of the ocean. Soon it was my turn at the front of the line.

My eyes fixed on the dancing gases, I met the sobering severity of the star of our show. The heat spread down my left arm and shoulder and I wondered silently what the true threshold was. How much could I take? How much did these firefighters take? As quickly as the burn began, it was time to rotate.

And then, one by one, a dozen aspiring firefighters emerged from the chamber, ominous charcoal smoke billowing behind us. We had survived Fire Ops 101.

I know that the greatest thank you I could give Dr. O’Shaughnessy for extending this invitation to me is to share the heroic work of our first responders with any and all of the people who might read this. His sincere wish is for people to use their time, talents and treasure to serve those who serve others.

But how do I thank the firefighters?

Some of the men and women who helped us that day were just coming off a night shift. Some came from other cities. They stuffed us into gear and adjusted our hoods and checked the seals on our oxygen masks like concerned first-time parents. They gave a group of pencil pushers an unforgettable opportunity to explore their perceived boundaries and abandon their comfort zones and walk in a hero’s boots. And yes, those boots were impossible to fill.

After feeling the weight of the Jaws of Life and the adrenaline in the air at the top of the ladder, it’s hard not think of the demands of their days a little differently. When you’ve given all of your energy to bring someone back or find them in a sea of smog and perpetual risk, you can’t discount the heart of the men and women under those helmets. And once you’ve stared down a wall of flames, and felt the unforgiving fever of their authority, it’s impossible to deny the bravery of the souls who wear the shield, and the price they’re willing to pay.

I cannot express my gratitude enough to our handlers, Chad, Jason and Brandon, the organizers and all of the firefighters who volunteered their Saturday to facilitate this life-altering experience. Like the beast you slay, you have my deepest respect. Your brotherhood is a beautiful thing to behold, and your courage knows no limits. I feel honored to have climbed where you climb, crawled where you crawl and to be able to say I dripped the sweet sweat of humility, and therefore found a new empathy, in your company. Thank you for your patience and your service, your humor and your heart. Thank you for risking your lives to save lives every day.