This post was written by Courtney Leach, digital/social media manager, Parkview Health.

As a little girl, I was what you would call a chronic worrier. I was a prisoner of my perception that we were all in danger, all the time. Nearly every night, heart racing at the illusory thought that a heinous bandit had broken into our house under the auditory guise of a temperamental icemaker, I would race down the hall to my parents’ bedroom, lay as straight as a plank of pine along the bottom of their bed, pull the overhang of their comforter around me for a bit of warmth and sleep on their floor, undetected next to our geriatric golden mutt, until dawn. As uncomfortable as the accommodations were, the sound of my father’s rhythmic snoring and my mom’s subtle movements made me feel invincible. This was their room, in their home, and surely they would protect any and everyone who entered.

As the years have passed, my fears, unfortunately, have followed me. Sure, they’ve evolved, but the general nag of worry is as familiar and persistent as it was in my childhood bedroom decades ago. The biggest tragedy perhaps, is that there are a lot of people wrestling with similar angst – consuming and processing headlines from our own backyards or not-so-distant neighbors, and trying to strike a realistic balance between preparedness and the pursuit of happiness. Life can feel like a game of chess, where the king, despite our most strategic efforts, is always vulnerable. At the end of the day, we all just want to feel safe.

Because when we feel safe, we experience ease and empowerment. When we feel safe, we find the space to explore and entertain both our obligations and our dreams. When we feel safe, we feel comfortable, to heal and to help.

In a hospital, safety is a constantly moving target. Each year, millions of patients, guests, vendors and caregivers pass through the doors of a Parkview facility. The safety and security of each and every soul is a top priority for the health system, and thus requires a dedicated team committed to ensuring people are protected.

With this great demand and responsibility in mind, in 2013, Thomas Rhoades, corporate director, Public Safety, Parkview Health, convinced the state Senate that the system needed its own police force. Now, five years later, I would have the opportunity to see this team in practice. Henry Mckinnon, deputy chief of police, Parkview Health Police and Public Safety, arranged for me to spend an evening in early October with Lieutenant Tony Knox and his second-shift team at Parkview Hospital Randallia.

2:30 p.m.

My first impressions of the lieutenant would hold true for the larger part of the nearly nine hours I spent with him that night. Tony doesn’t like to waste time. He spoke fast. He walked fast. And when he was done speaking, which he typically signaled by saying, “Does that make sense?”, he expected me to be fast with a follow-up question. It took about five minutes for me to realize that Tony challenged everyone around him to be better, whether he’d known them for years or far less. Always one to acclimate, I decided I better start writing shorthand, picking up the pace and brainstorming in his brief pauses if I wanted to keep up.

Our first stop was at Security Post No. 2, located in the Emergency Department (ED) waiting area. This is where the team keeps patient valuables in two separate safes, as well as a lost and found. “The things people leave behind most often are glasses, hearing aids and dentures, and we don’t handle those,” Tony explained. The officers maintain a three-part documentation process for the valuables, and check the inventory three times a day. After 30 days, any unclaimed money goes to the Parkview Foundation.

As he flipped through labeled envelopes, I learned that Tony had been with the Parkview police force for three years, always on second shift (3-11 p.m.), which he explained, runs hot and cold, but typically keeps him and his team very busy. “This was my retirement job,” he smirked. Tony joined the Indiana State Police in 1987. He volunteered after Hurricane Katrina, went undercover for a year, and started working with his first police K-9 dog in 1990. He became the K-9 program coordinator in 2006, and kept the position through his retirement in 2016. “I figured I’d work here for a few years, but the Parkview family is just so great.”

One of the things he’s proudest of is the mentoring the team does. “We have a great crew made up of people who lend their time and talents to help others. And they’re all about building relationships. Patients who have gone through their share of struggles, will pop in just to say hello to us. That’s what a community hospital does. You have to remember; we have five people covering a facility with a population about the size of Garrett. Everybody’s heart has to be in the right place.”

That means adapting and assisting, without judgment, even in the most difficult of situations. “We do get a number of gunshot wounds and stabbing victims. They often get dropped off at valet. I always tell my guys, it’s very likely that this person is having the worst day of their life. We have to do our jobs, but we also have to consider what the patient is going through. Show me a perfect person. There isn’t one.” The team will take over the valet area off of State Street later this month, in an effort to implement new procedures for incidents, like these, where security is imperative.

We walked through the electronic doors back to the Emergency Care Center (ECC). The ECC desk is located next to Area 4 in the ED. This is where emergency psychiatric services are provided, and a number of rooms are equipped with locked doors and video surveillance. Because Randallia supports Parkview Behavioral Health (PBH) and Park Center, this area is often at or above capacity. The team spends the majority of their time supporting staff on these rooms and the additional rooms used to accommodate patients who are experiencing mental health distress.

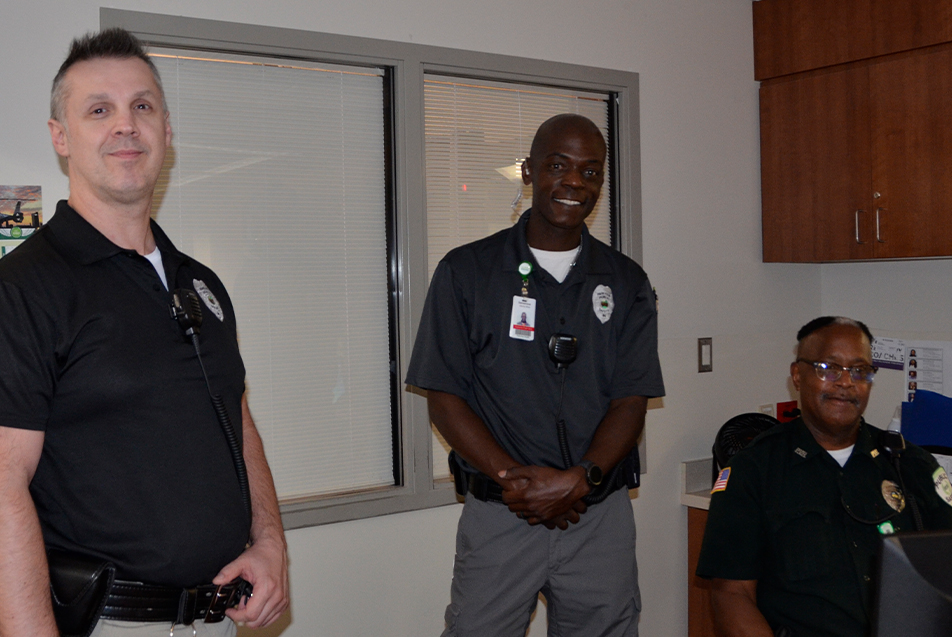

Tony introduced me to Demetrious “Deke” Allen, who was sitting behind the desk, eight admiral blue folders laid out in front of him. Each file contained the details of a patient who was currently “on watch” and required close observation. Deke is a man who wears a lot of hats, a common scenario with this group. He works at the post office, as a firefighter in Huntertown and as a public security officer (PSO) for Parkview.

“I love my work because I never know what’s going to happen,” Deke said. His role at the fire department often resembles his responsibilities in the ED. “We get a lot of combative patients, and I have to be alert and stay on my toes.” Like many who join the Parkview team, Deke is hoping to one day go through training at the Indiana Law Enforcement Academy (ILEA) and become a police officer. “Anyone can get a job. I want a career.”

There aren’t many differences between a PSO and a police officer. A police officer carries weapons and can make a legal arrest, but the PSOs are given a significant amount of authority. As Tony would later tell me, “I trust my PSOs to put their hands on people if they need to. They are an extension of me.” A number of Parkview PSOs have been recruited to go through ILEA and become police officers, either for Parkview or another force. The last four recruits to the Fort Wayne Police Department (FWFD) were from Randallia, a fact Tony celebrates. “We want people to get to the next level,” he said. “Whether that’s within Parkview or outside of it.” He attributes some of his teammates’ success to the nuances of their location. “We see a lot here. This facility isn’t for everyone, but it will prepare our officers with the people skills and the de-escalation strategies that give them a leg up.”

Tony discussed de-escalation quite a bit during our time together. “In my old job, backup might be 25-35 minutes away, so de-escalation was incredibly important. But it’s different in this setting. We’re not trying to gain compliance; We’re trying to get a positive patient outcome. That’s the heart of everything we do here.” One tactic the group uses often is restraints. They do quite a bit of training on how to apply the apparatus quickly, safely and effectively. “We have to use restraints more than most areas of the health system, and we have less injuries compared to other shifts or locations. I take a lot of pride in that. We do as much as we can as a team and overcome by numbers, rather than strength.”

The value of training and teamwork were common threads in my discussions with the group. “It’s like any relationship. We have to communicate, even in stressful situations,” Deke said. “Things can go south fast, and if we don’t talk to each other, we could be in trouble.” That includes communicating with nurses, doctors and others on the care team.

Perhaps the only thing that ranks higher than patient outcomes for Tony is staff and facility safety. “It’s always a balance,” he said. “We don’t want anybody to get hurt. If we train ourselves and our coworkers, then injuries go down. There’s no doubt that training increases safety.”

Leaders want all co-workers to go home the same way they came in, and for Tony, that means “preparing with purpose”. New hires will go through 4 hours of training on handcuffing alone. They will also do 1-2 hours on restraints and body holds. Tony has made adjustments to the methods Parkview officers use based on the latest research and findings implemented for other life-saving tactics, such as CPR. “We want to leverage our body’s power so we can work smarter not harder.” None of this, however, is a replacement for experiencing true patient interactions.

“You can talk about it, learn about it, but until you actually see these things and have to respond, you can’t understand,” Deke said.

Each team member will also be placed in restraints so they can see the patient perspective, an exercise that has proven to be smart kindling for fueling a higher degree of empathy. “Perception is more important than reality,” Tony said. “Even if you aren’t feeling empathetic you can still act in an empathetic way. It’s about respect.”

Throughout our conversation, Deke’s eyes never stopped scanning the screens in front of him. He was responsible for monitoring the unpredictable actions of eight patients. At shift change, Deke would go over a pass-on sheet, a document that explains which patients are in which rooms as well as their tendencies. This is one method for getting everyone on the same page. The team also holds a 15-20-minute briefing in the squad room each day.

A call came in to assist with lifting a patient receiving a CT scan. Tony and Deke were both on their way within seconds. Once Deke saw that Tony could assist, he quickly returned to his ECC post. This was an exercise that happened often for the officers. They were experts at triaging the most emergent need and allocating the appropriate manpower while maintaining overall security for the facility.

4:30 p.m.

Someone screamed and everyone’s heads turned. “That was from pain,” Deke said. You start to sense the sentiment behind the sounds in the ED, based on volume and the activity of the hive of helpers formed around the patient. It was skillset acquired over shifts and through sharpened senses.

There was a call for a transport to PBH. All individuals on 24- and 72-hour holds are escorted in handcuffs, for the safety of the patient and the officer. “It’s tough, because we definitely don’t want to criminalize mental health,” Tony said. “As I escort them to the car, I always tell them to ask questions. This is a new experience for a lot of them, and it’s important that they understand what’s happening.”

When a new patient comes in, the security team will bag and secure their valuables, and offer a locker to loved ones. “We take anything that would distract them from care – a smartphone, laptop or tablet – but we don’t do a thorough search. We want to give people the benefit of the doubt. They are here for medical reasons,” Tony said. “We work hard to find that balance between respect and protecting others.”

In different ways and at different times, each team member I met expressed heartache for the epidemic they see on every shift. “If we build more areas for mental health, we will fill them,” Tony said. Between the opioid crisis, high suicide rate and general rise in mental health distress, the need for psychiatric services is greater than ever before.

The Crisis Intervention Teams (CITs) bring the majority of mental health patients to Randallia. Tony believes this is because of access to PBH, an experienced staff and efforts internally around supporting doctors and assessors.

Eric Bucher, who has been with Parkview for five years, two as a PSO and three as a police officer, arrived to transport the patient. Because this particular individual had expressed some aggression toward Eric, Tony assisted in walking him to the patrol car. I watched through the sliding doors as the men spoke gently to the patient, no doubt offering guidance and well wishes for his days ahead.

As soon as Tony returned, a nurse approached the ECC. Her patient was going to have to stay and wasn’t very happy about it. Without missing a beat, Tony walked into the room to help the pair of caregivers. He offered to grab equipment and personal belongings, whatever they needed to make the move a safe, smooth transition.

Later, as we spoke about the scope of the team’s responsibilities, Tony painted a clearer picture of their amplitude. “A lot of what we do is tangible. People can tell that we were there. But a lot of what we do, no one will ever know. We’re a catch-all. If someone needs help, we’ll be there.” This has included mopping, making beds and jumping in to relieve other team members doing compressions. “If there’s an RHC (Respirations Have Ceased) call, we’re definitely in there to offer support. If loved ones need a private room or chaplaincy, we’ll help with that, too. We want to be a strong resource for the entire hospital.”

And sometimes the gesture is subtle, but substantial, as Deke shared, “I just sat in the lobby a few days ago with a child so his mom could go to the restroom. I was joking with him, asking him questions. I mean it was a small kid, and it’s a big world. I just wanted to help him find some happy.”

5:30 p.m.

We took a series of right and left turns and ended up in the Dispatch Center. A handful of staff members take all of the calls for the Parkview facilities as well as Samaritan from this location. Last year, the security team received 35,000 details, and are on track to surpass that with approximately 50,000 details this year. Tara Richards, supervisor, Public Safety Communications, observes a number of views on a wall of screens and dispatches for patient, guest or staff assistance, collection of valuables or blue light calls from the parking lots. The team will also receive anonymous security tips or alerts from local law enforcement regarding patients with warrants. Tara passes these details along to the security team through their radios, which they typically wear in their ear.

In incidents where a patient’s arrival could potentially pose additional threats, the team is prepared. If a gunshot wound victim is taken to the facility, for example, security would initiate a lockdown. They secure family and friends in one area and monitor for activity, inside and outside of the hospital. The police officers do have the authority to arrest people, just like any other police officer. If someone is being disruptive, they can be removed from the property or taken to jail. “If someone interferes with patient flow and care, we will do what we need to do,” Tony shared. “That being said, we always try to give people plenty of chances. They’re often in highly emotional or uncomfortable situations.”

As we stood up to leave, Tony received word that the patient he’d helped transport from the ED earlier was agitated and the situation had escalated. By the time we arrived, the rest of the team was already standing outside of the room. This was the first time I met police officer Shane Lee. When I remarked about their quick response, he mentioned the importance of being familiar with the facility. “You never know where you’re going to be needed, and you want to get there fast.”

6 p.m.

Since we were already on the second floor, Tony decided to do some rounding. He makes being seen a top priority, and says hello to everyone he passes. “When people see us, they think of us. I subscribe to the 10-5-1 rule,” he said, “which means that within 10 feet of a person, I’m making eye contact, within 5 feet I’m saying something and within 1 foot I’m introducing myself by name. I tell people, if there’s a problem, come get me.” When I asked if people ever appear intimidated by him, the corners of his mouth turned up ever so slightly. “People will say, ‘I hate cops,’ and I’ll say, ‘I do, too.’ Hey, I get it. But it’s my job to change that perception. Remember, perception is reality.”

He also looks into each room and makes eye contact with the nurse. “I know most of the clinical staff well enough that I can tell pretty quickly if they need me. They have to be able to do their job, and I’m comfortable being the ‘bad guy’ if I need to in order to enforce the rules and keep everyone safe.”

But of all the tools in the shed, strong-arming certainly isn’t Tony’s favorite. He much prefers voluntary compliance. “It’s about building a rapport so that people want to do the right thing,” he explained. “For example, not that long ago, we were changing the parking guidelines. So, we put candy on top of a stack of maps. When co-workers would come over, we’d start a conversation and then talk about the new expectation. It gave us the space to have the dialogue.”

If candy is the key to engaging co-workers, for Tony, it seems the eyes are the window to establishing trust with patients. “We get down to their level and never stand over people. With everyone, but particularly with kids, I tell them, ‘Look into my baby blues.’ When they look into my eyes, I want them to see empathy. I tell them I’m there to help and then I show them I am.”

Another foundational block to building conversation is having things to talk about. Tony, who is an avid reader, encourages all of the men and women on his team to read whenever and whatever they can. “The more you read, the more you know. And the more you know, the more likely you’ll have something to talk to someone about.” It all adds up to a connection – one built on commonality rather than intimidation.

7 p.m.

Security officer Dwight Robinson had taken over the ECC desk, and was down to five watches. Dwight is one of those people who doesn’t know a stranger. He’s been with Parkview for 12 years, and was a firefighter for 20 years before that. He played football at Purdue and wanted to go pro, until an injury pushed his dreams to the sideline.

“Life’s like a puzzle,” he said, as he walked me down the unexpected turns and detours of his professional path. “God gives you all the pieces, but you have to figure out how it all comes together. It may be five years later when you realize an important piece was sitting right next to you all along. God put me in each of my jobs.” Dwight, who believes that working with your hands in the greatest form of therapy, has a farm with horses and enjoys leatherworking in his spare time.

He was keeping his eyes on two juvenile patients in Area 4. One was talking to the other and getting him worked up, making them both risks for elopement. This, I was told, is very common.

Tony teaches the team to view these, and all situations, through the lens of anticipation. They aren’t just watching what the patient is doing, they’re anticipating what they might do next. Where they might go next. Anticipation keeps them ahead of the curve. “I want them to ask things like, ‘Who is this person?’ ‘What did they bring with them?’,” Tony said. “There’s no such thing as a ‘routine’ patient or scenario.”

8 p.m.

A call came in that a patient was agitated down the hall. Tony was gone before I even made it around the ECC desk. I knew I’d never catch him.

I pulled up a chair and watched on the screen as Megan Kariger, MS, CCLS, certified child life specialist, got down on the floor to work with one of the young patients. She offered games and patience, but despite her best efforts, the young man still appeared unsettled. Tony returned from his call and went straight into the room. I looked on as he got down with the child and folded a paper football. The situation, at least for now, had been diffused. “Tony’s good,” Dwight said, reading my mind.

As Megan walked out to leave the ED, she turned and looked over her shoulder. “I’ll have to steal that trick from you!” she joked to Tony. He smiled and waved.

8:30 p.m.

A lot of people don’t realize that, once Chaplaincy has completed the necessary paperwork, Parkview security is responsible for transporting patients after they pass away.

Admittedly, this isn’t a task I witness every day. I stood with my back against the wooden railing in the Supportive Care Unit and watched as Eric and Tony tied the backs of paper gowns on each other. They went into the room and gently shut the door behind them. I chose not to go in. The floor was so quiet, aside from a few whispered conversations and sporadic monitor beeps. I looked down at my hands, unsure of what they should be doing. Without consciously making the decision to do so, I began to pray. I said a silent, brief blessing to the people who loved and had been loved by the person behind the door.

The handle turned and Eric and Tony came out. We rode the elevator down to the morgue where Tony filled out the burial transit permits. “No one ever does this alone, and we always maintain the patient’s pride and dignity. Always.”

The somber responsibility brought us to discussing more emotionally taxing instances. “Being a first responder is a calling,” Tony said. “But I tell my team, you can survive a gun battle, 15 seconds of adrenaline, but what’s your plan to survive the year after that? And the year after that? We talk a lot about mental health. We debrief after everything we do, formally or informally. I push employee assistance services quite a bit. When you take care of yourself, the ability to care for others follows and becomes easier.”

The sincerity of his concern comes from both hindsight and humility. “When I was young, I thought that, since I’d trained, I would be OK. Now I realize I was just lucky,” he said. “I was good at a lot of things, but not as much in here.” He tapped his heart.

10 p.m.

We went back to Security Post No. 2 to eat dinner and wrap up our time together. Police lieutenant Greg Wajer came in, a little early for his 11 o’clock shift. Greg has been with Parkview for five years. He joined after serving in the Army, a fact that can be helpful for patients with PTSD or other ties to the military. “Sometimes it’s helpful for people to know I have that background, and sometimes it isn’t,” he said.

“Different officers connect with different patients,” Tony added.

I had been talking to Tony about the stigma that seems to follow police officers, and I invited Greg to weigh in. “To do this job you can’t take anything personally. Policing here is different. If you come in thinking it’s the same as the streets, you will fail. There’s a customer service element to this.”

Tony nodded, “You want to be in a leadership role without anyone knowing you are.”

One of the biggest struggles is just getting people to recognize their group for what it is. “Most law enforcement is on a 10-year cycle before it’s truly accepted, so we’re getting there,” Tony said, but the lack of awareness can lead to confusion among the staff. “We’ll have co-workers call the local law enforcement and we’ll be standing right there. But we get it. It takes time. That’s why we don’t wait for people to ask for help. We walk toward it.”

When Greg learned that I was shadowing Tony for a story, he was quick to turn to praise for his fellow officer. “I’ve taken a lot from what Tony’s given me,” he said. “We do a lot of training together.”

That training includes teaching situational awareness classes to the community. While Tony’s two grown daughters were the first beneficiaries of his vast knowledge of self-defense, they certainly aren’t the last. Tony is a wealth of warnings and smart solutions, and I was happy to run a few scenarios by him.

For example, if you, like me, are a runner, a lock on a solid lanyard and a handheld tactical pepper spray gel are the perfect combination for creating space between you and a perpetrator. Or, if you, like me, select a spot next to the shopping cart return in the parking lot, you should be aware that, not only are you more likely to get dings in your vehicle, but you are also less aware of people approaching your car and posing a potential threat. He had suggestions for so many situations … Use the panic alarm on your key fob as a security warning at night, if needed. Don’t park next to a big van or box truck that might block your car in a security camera. My perception of danger, he assured me, was a good thing, but making a plan was much more productive.

But Greg hadn’t come in early to discuss these pedestrian precautions. He was there to congratulate Tony on his new appointment. Earlier that day, it was announced that Tony was named captain at Parkview DeKalb Hospital, and everywhere we went, we were trailed by a cascade of well wishes. His first day at his new post will be November 3.

“The staff is really going to miss him,” Eric told me. “We have a lot of respect for him.” His transition would be a bittersweet change for many at Randallia.

When I asked Tony how it felt to know his team was so fond of him, he deflected, in a perfectly impactful way. He was good at that. “I just want everyone to do their best,” he said. “I’ve never been anyone’s crutch, but I’ve happily been their guide. In case you couldn’t tell, I’m very purpose-driven, and we talk about goals a lot. Everything should have a purpose. When you leave at the end of your shift, there’s a sense of accomplishment. If not, you didn’t show up.”

I wanted to know how he’d done the job for so many years and maintained such an optimistic outlook on serving others. “It’s all about having a positive attitude. What you dwell on is what you become. We see so much sadness sure, but also so much success. The difference is what you carry with you. You have to ask yourself how you made a difference today.”

Tony loved to ask me questions like, “Do you love everyone the same or hate everyone the same? What’s the difference?” I was convinced there was a psychology major buried somewhere in his past. He admitted he was given a gift for reading people, like the friend who hadn’t told anyone she had cancer, but Tony knew. He just sensed she was acting differently. In one shift, he had challenged me to think about things differently. Not just safety, but the human connection.

“There’s no way to measure what we do,” Tony said, “But if everyone’s safe at night, I’m happy. That’s success, even though it’s often things you don’t see.”

Sometimes, we don’t realize what we need the most until it’s threatened. We don’t understand the sacrifices and service others provide in order to protect our peace of mind. While I don’t argue that Tony’s team’s efforts are difficult to quantify, I would argue they aren’t always invisible. As I pulled out of the parking lot that night, under a quartered moon and canopy of fluorescent lights, I happened to glance back through the glass where we’d just said our goodbyes. And I saw Tony there, watching me back out, making sure I was OK. And I knew. I knew that Parkview was his home, and he would protect any and everyone who came through its doors. And I was grateful. Grateful to feel … safe.