This post was written by Courtney Leach, social media manager, Parkview Health.

5:30 p.m.

I put my plate in the dishwasher, grabbed something sweet and kissed my girls goodbye. “Have a great time on the night shift!” my oldest yelled over her shoulder, not bothering to look away from “Stranger Things” unfolding on the screen.

The weeks-long stretch of muggy, suffocating humidity had finally broken, and the evening air felt almost pleasant. I plugged my destination into the app, turned up my music and headed toward Kendallville. Just outside of my neighborhood, a mere three minutes into my commute, I spotted flashing lights heading toward me. I pulled to the right and gave the mobile ICU, which I recognized from a previous ride along, the road, a courtesy firmly embedded in my driving etiquette.

6 p.m.

I parked outside of the Kendallville station, directly across from Parkview Noble Hospital, and pulled on my backpack straps. “Are you? … Who are you? …” a curious EMS team member inquired, eyeing me skeptically.

“Am I riding with you tonight?” I asked, the pep of an overcaffeinated poodle coursing through my pitch.

“No, definitely not,” she replied quickly. “I think you’re in the wrong place.”

We were off to a great start.

“Are you Chantey?” I countered. She was not.

“Chantey and Hunter are at Cromwell tonight. You need to go there. You’re going to want to go to 6 until it Ts into 9. You’ll see a gas station on the corner and a … what is it … a …”

Another first responder chimed in with more potential landmarks.

“Do you happen to have an address I can put in my phone?” I asked. (I am many things, but a strong navigator is not one of them. She’d lost me at “Go to 6.”)

6:30 p.m.

The drive from Kendallville to the Cromwell station is a parading picture show of Hoosier farmland and rural property. I followed the sharp curves through Brimfield and Wawaka, towns where neighbors are farther away but always close by.

On a corner surrounded by bean fields, I spotted a building with two tall garage doors and an American flag at half-mast. This, I thought, must be the place. I rang the bell, but no one answered. I tried once more. I assumed they were out on a run and sat down on the plastic picnic table outside to wait.

My notes for the next 20 minutes read like a page from a discarded Thoreau first draft. If you’ll humor me, “Playful sparrows are swooping and chasing each other overhead. I hear the crickets, the gentle flapping of the flag in the lazy late-summer wind. A train passes over tracks behind the tree line along the Cromwell countryside. Hundreds of thousands of beans blend into one vast textured viridescent carpet blanketing as far as my eyes can see.”

Sporadic, scattered beeps and messages from dispatch would occasionally penetrate the closed garage and pull me from my sappy rumination. At last, the familiar green logo came around the corner.

7 p.m.

Before they were even out of the ambulance, I was standing in the open garage smiling, pen to paper, eager to hear where they’d been.

“We aren’t Chantey and Hunter, either,” the paramedic in the passenger seat said, as she descended the steps from the van. “We’re covering here until they get back from a run. We wanted to come and let you in.”

I followed her inside. At first glance, the Cromwell station reminded me of a shared dorm space. There are two desks with computers, a kitchen along the wall, with a refrigerator, microwave and stove, a matching set of worn lounge chairs, and a table with plastic desk chairs. There are two bathrooms and a single bed in the back as well.

In between charting, Natalie Gibson, paramedic, an eight-year veteran with Parkview, generously indulged my questions while also troubleshooting a temperamental printer. Her and her partner, Garrett Helpling, paramedic, who joined Parkview EMS in February, were closing in on the end of a 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. shift, universally regarded as the busiest, and had floated to Cromwell to ensure the area had coverage. The pair were on Medic 54, the friendly vagabond of the Noble fleet, used to cover the territory as needs fluctuate.

A dispatcher gave instructions from a speaker over my shoulder. “Is that for you?” I asked. “It seems like there are tones and voices coming from everywhere in here!”

She laughed. “What you’re hearing back there is county dispatch. We’re really listening for Parkview’s dispatch, which comes in through the overhead speaker and our radios. Our dispatch makes the call on which team needs to respond based on the details they have. At first, the radios just seem like a lot of noise, but you catch on.”

I knew I was a rookie, because it did, in fact, just sound like a barrage of high- and low-pitch tones at varying lengths followed by directions at assorted volumes. Natalie closed down the chart she’d been working on and picked up her radio. “It was so nice talking with you. It looks like Chantey and Hunter are here. Hope you have a great experience!”

7:30 p.m.

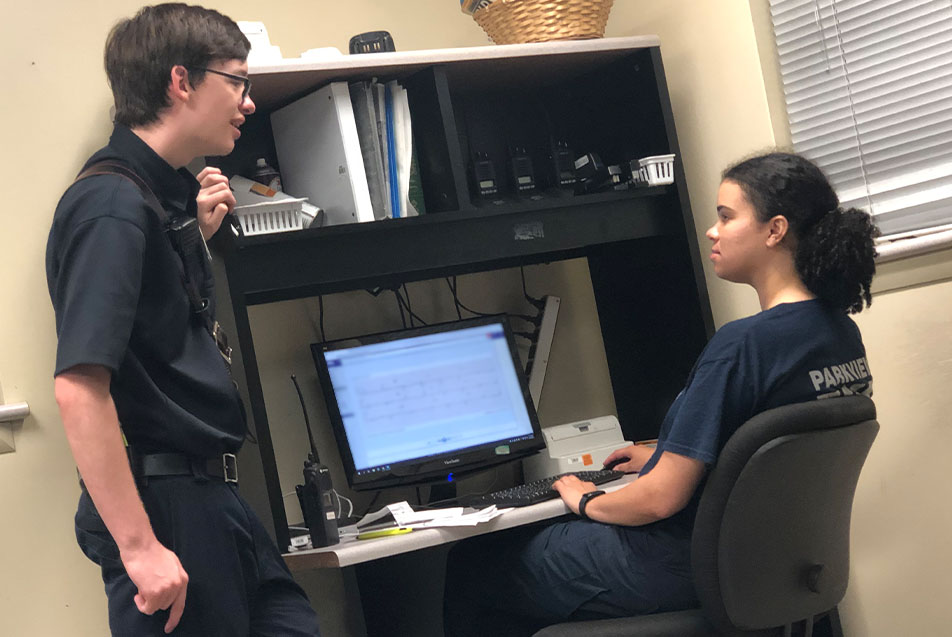

Chantey Baker, paramedic, greeted me warmly and introduced me to her full-time partner since January, Hunter Dunnuck, EMT.

Chantey has been with Parkview for nearly three years. “I had experience in the medical field, as a manager for group homes for the disabled. I saw EMTs a lot in that setting, so I had an idea of what they did. I was ready for a lifestyle change, so I decided to go to Ivy Tech and get my EMT certification,” she said. Chantey started as an EMT for the health system and worked while completing her paramedic license. She chose the night shift because it complemented her classes, which were 8 a.m. to 1 p.m., and never left. “A lot of caffeine and cat naps,” being the secret to her success.

Shortly after she started as an EMT with Parkview, Chantey decided to join the Aboite Township Fire Department. “I started a month before COVID hit,” she said. “They ended up taking us off the schedule since we were just observing at that time, and they didn’t want the added risk. Now I’m part-time there.”

Hunter has been a volunteer for the Columbia Township Fire Department in Whitley County for more than two years and also started his career during the pandemic. “My earliest childhood memory is of me tripping and passing out at my grandparents’ house,” he shared. “The paramedics came and helped me. Throughout my life I’ve seen what they do. My high school in Columbia City had an EMT program, so I took the prerequisites my junior year and started the class in 2019. I ended up completing the course from home.” Parkview offers an EMT program like the one Hunter participated in at Huntington High School as well.

In addition to the class, participants were required to complete 24 ride along hours, 10 patient interactions and 8 hours in the ER. “I did 300 ride along hours,” he said, fondly recalling his time with the crew at Parkview Whitley. “I got a temporary EMT certification, which was unique because of COVID. When Parkview hired me, I had to drive two hours to the nearest location to take the test to become an official EMT. I started around Thanksgiving 2021.”

While both admit it was interesting to start their careers during a global pandemic, they had the advantage of not knowing any different. “It was a lot to handle, but everyone caught on quickly,” Chantey said. She ended up getting the virus in early 2022, just after completing her paramedic license. “Here I was, so excited to start in my new role and I had to wait ten days because of COVID! I was OK, though. I had a lot of nausea, but that was it.”

Of the three EMS stations in Noble County – Kendallville, Albion and Cromwell – the latter tends to be the quietest. That said, it’s incredibly important to ensure that Parkview EMS has emergency vehicles positioned in close proximity to residents throughout the county, and the three locations make that possible.

Each emergency transport vehicle is staffed by two first responders. These team members can be of various levels of training, and can therefore, deliver different levels of care.

Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) – EMTs have the skills needed to stabilize and safely transport patients for all levels of emergencies. They can administer some medications, including Narcan, nitro and oxygen, and provide life-saving treatment onsite and in transit to a medical facility.

Advanced Emergency Medical Technicians (AEMT) – AEMTs have the same training as EMTs, but can also administer additional medications, give fluids and utilize some of the more advanced life-saving equipment on the ambulance.

Paramedic – Paramedics provide advanced medical care for critical patients. This includes triage with sophisticated medical equipment, starting an IV and administering a variety of drugs.

Chantey and Hunter are on Medic 53, a Mercedes-Benz Sprinter emergency van. Medic 51 and 54 primarily stay at the Kendallville station, and Medic 52 is stationed at Albion. If you’re looking for a thorough tour of the vehicle, Hunter is the man for the job.

“Everything has a purpose and a place,” he said, “and usually it’s within arm’s reach.” While the corridor in the back feels narrow, it is packed with utility. If a patient requires basic life support, Hunter will ride in the back, but if they need critical care, Chantey oversees the patient on scene and during transport.

He took me through the equipment and supplies, from the back of the van to the front. The average EMT course is six months to two years long, and it takes every bit of that time to learn the tools necessary to save a life. Every bag is designated to a set of circumstances – cardiac event, pediatric case, general first response, etc. Every shelf holds the remedies to a crisis – trauma, airway, etc. Everything is color coded, conveniently located and designed for speed and ease. Some of the equipment on the van gets used more than others, but everything stays. “We have things for high acuity, low frequency events, like a mass shooting. You don’t know when you’ll need these items, but you want to be ready in case.”

It's imperative that both partners know the layout and inventory of the van. Hunter might not be able to utilize everything on board, but he has to be able to locate items and get them to Chantey quickly if she needs them.

After she finished charting for their 6 o’clock run, Chantey came out and joined us in the garage. I asked what they liked most about their work. “Everything,” Hunter said in his succinct style.

“I like being outside,” Chantey offered. “And I like that every day is a little different.”

“That has to be challenging, too,” I countered. “Not knowing what you’re walking into.”

“There’s a lot of problem-solving in what we do,” Chantey said. “We are facing a different situation, in a different environment, with different people on every single call we answer. There might be pets, bystanders, hysterical loved ones, and our job is to care for the patient, but also talk to a lot of other people.

“I was really timid when I first started. I struggled with small talk and communicating to patients. But now, I’m much better at it and I understand why it’s so important. We are advocates for patients. We are really good at explaining things to them and getting them the help they need. You would be amazed how many people call 911 or have a loved one call, but they don’t want to go to the hospital. But that might be just what they need. Sometimes we might need to involve the ER physician, or walk them through things several times, but we are always going to try and advocate for that patient.”

Walking into different situations is as daunting as it is stimulating. First responders always have to trust their instincts and rely on others with special training. “Safety is a top priority for us. The goal is to get everyone through a call as safely as possible, so if we feel something isn’t right, we can always involve the police,” Chantey said. “People think that EMS works alone, but in Noble County, we work closely with other first responders, including the fire department, law enforcement and volunteers. The first responders in our area are great at making initial assessments. We communicate really well and listen to each other when we have ideas or concerns. Which is better for the patient.”

But in emergency medicine, there will always be runs that don’t go as all hope. “We see things no one should have to see,” Chantey said. “Parkview has a great Employee Assistance Program, and our co-workers and managers are all really close. It’s rare that you would call and no one answers, even on the night shift. I’ve been on the phone for hours with a co-worker after a tough run. We are all there for each other. But it’s those calls when you really make a difference, when you save someone’s life, that give you that high to come back and do it again the next shift.”

For Chantey, one of those big wins was a trauma patient she helped on a particularly upsetting run. “I was called to the scene of a mass shooting, and I helped a patient who had two gunshot wounds. I was able to stabilize the individual and get them to Parkview Regional Medical Center. A few months later, I was going into Parkview Noble, and the patient was walking out with a cane. The patient was able to express their gratitude and it was so reaffirming that this is why I do what I do.”

The bugs found us under the iridescent glow, and we decided to move indoors. More high- and low-pitch sounds came from above and beside. Each time, I sat up and watched my subjects for cues. And each time Chantey smiled warmly, unmoved, and told me, “That’s another county.”

First responders are a breed well versed in the waiting game. While there are only so many tasks team members can tackle to pass the time, Chantey and Hunter like to use it to manage expectations, anticipate scenarios and improve their communication. “We try to plan ahead,” Chantey explained. When we have limited information about a call, we start at the worst-case scenario and work backward, from most to least life-threatening injuries. We talk about who would do what and develop a general plan so that we have a roadmap when we get on scene. Now, of course, that can change, but at least we both have an idea and can use time to the best of our ability.” There’s also a lot of talking on the scene. “I’m often telling Hunter what I need, but he’s also very good at anticipating and having things ready. We work really well together.”

Midnight

Tones. The tones.

A call came into Noble County. Now it was just a matter of where in Noble County. Medic 51 was already out. After a suspenseful pause, dispatch instructed Medic 52 to report to the scene. Since this left one team to cover Noble County, Medic 53 (us) needed to relocate to the Albion station so that we were in the center of the coverage area.

There are an infinite number of “If … then …” scenarios in the EMS world. This applies to things first responders face out in the field, as well as where they find themselves on a given shift. Noble County is 417 square miles and Parkview is committed to having emergency responders available in a timely manner in a resident’s moment of need. To achieve this, ambulances often relocate. If Medic 52 gets a call, no one has to move. But if Medic 51 (in Kendallville) and 52 (in Albion) get a call at the same time, that leaves a lot of miles between a patient in Avilla, for example, and Cromwell. So, the team in Cromwell moves over to close the gap.

Hunter ran through some of the other potential scenarios as he gently adjusted the steering wheel to maneuver around the bends in the road. Fog was just starting to settle in over Noble County, and I stared out at the glow of the waxing midnight moon.

I took the opportunity to ask how they decide whether to use lights and sirens, and Chantey shared that the measure requires some caution. “People don’t really know that lights and sirens are actually a big risk to us,” she said. “Other drivers don’t really pay attention to us, and intersections and cross streets can be incredibly dangerous. We have family members who will try to follow us, and they’ll blow through red lights, putting themselves and others in danger. Being out here, at night, with limited traffic, the payoff isn’t that great for lights and sirens. It can be best to just come and go from a scene quietly. It depends on the situation and is really at our discretion.”

1:30 a.m.

Standing by for a run is much like being stuck in an elevator with a group of strangers. You don’t know exactly how much time you have together, but you don’t really have anywhere else to go. So, you talk. And by 1:30 in the morning, you start talking about anything that will keep you awake.

Once we’d covered the ins and outs of the van, the equipment, the respective roads that brought Hunter and Chantey to EMS and the general workings of Parkview’s first responder program, there was a lot of space left to fill. Which, as someone who makes a living asking other people questions, I didn’t mind at all.

Chantey, for example, has an affinity for her turtle (who she occasionally takes on walks) and two red-footed tortoises. She’s rewatching Grey’s Anatomy – though she confesses there are a number of inaccuracies – from the beginning.

Hunter is a jack of all trades. He is well versed in instruments and music composition, computers, video games, film editing, general tinkering and the list goes on and on. He is a walking encyclopedia brimming with details about county populations, emergency protocols and a wealth of miscellaneous categories. (An ideal Jeopardy! candidate in my opinion.)

When they don’t have a Marketing team member hanging around peppering them with questions, they often pass the time watching shows, catching naps or enjoying some silence. And on a slow night, that’s a lot of silence, interrupted only by the bouquet of dispatch sounds sporadically piercing the monotonous hum of an aged refrigerator.

In our idle time, I asked Chantey what lessons she’d gleaned from others in the field. “There’s a lot behind the scenes when you’re caring for people,” she began. “Sometimes you need to make food or clean up a mess, or help someone get dressed or get out of a sticky spot. We’re all human, and it could easily happen to us. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen first responders run to the store and buy a pop or candy for a diabetic patient who needed it, with money out of their own pocket, because they care about what they do. Sometimes cleaning up a mess or helping them get covered to spare them any unnecessary embarrassment makes the biggest difference.”

We talked about humility and how vulnerable her patients often are, frightened and uncertain, maybe alone or with their loved ones looking on. “Everyone is experiencing their own emergency. That’s why they call us. You have to remember that and treat each person with compassion.”

3 a.m.

Tones. The tones.

And this time, it was for us.

There’s a very specific, yet indescribable energy in the air right before a storm. It’s electric and frightening but exciting at the same time. It’s an anticipatory exhilaration that makes you want to simultaneously stare and flee. To peer and to protect yourself. That’s the only way I know to describe how it felt riding in the passenger seat through the fog in those early morning hours. I was instantly as awake as a person can be. Every sense felt heightened, suddenly so aware of the enormity of this job.

The request was no lights and sirens, so we went quietly to the scene. As co-pilot, I had to help Hunter navigate somewhat, though he only asked for assistance once. The blue line on the map kept getting shorter and shorter. We came around a corner in a residential area and saw a handful of vehicles with their lights on – volunteers for the county, Albion Fire and Rescue, and local police.

Because of the nature of rural communities, it’s not uncommon for other first responders to arrive before the Parkview EMS team. This is where the collaboration and communication come into play. The first responders, in the clothes I imagine they had been sleeping in just prior to hearing dispatch, had already started getting readings for the patient. They were so kind, so reassuring. As Hunter said, “Everyone at a scene is useful.”

The patient needed to be taken in for further evaluation and treatment. Patients are given the option of where to go in most situations, but the critical nature of their condition could impact the team’s decision. “If they are severely critical, a trauma is activated and a surgeon is waiting, we’ll take them right to Parkview Regional Medical Center,” Chantey explained. “If they prefer to stay local, they can pick where they want to go. We often consult with the ER physician on call for guidance if we aren’t’ sure, but over time you become pretty familiar with the resources at each location.”

The group of first responders brought the stretcher in and got it ready to go so that Hunter and Chantey could focus on caring for the patient. They worked as a group to get the individual onto the stretcher, through the door and onto Medic 53. I sat in the front (to ensure I didn’t get in the way) and listened as they hooked up monitors, oxygen and started the IV.

They were using every bit of the space they had, working separately but together. Wasting no time. The patient’s roommate came out with their wallet and asked me if we could take it for them. A wallet … such a practical need on a morning that likely felt entirely petrifying for this person.

Hunter told me I could sit in the back, at the head of the patient, to get a better view of Chantey working.

“How are you feeling?” she’d ask. “Any change?” “How can I make you more comfortable?”

I could feel the rumble of the ground passing underneath our feet, every pothole, every patch of loose gravel. The plastic sliding doors vibrated against each other, the orderly supplies jostling gently against them. Chantey was laser focused, pulling strips of paper from the monitors, taking notes, asking questions, retrieving medication she would need if she didn’t see the change she wanted.

The back of the ambulance is an exercise in extreme concentration and multitasking. Information is coming in, being exchanged, constantly changing. Reactions have to be quick but deliberate. Decisions can make all the difference.

“We’re ten minutes out!” Hunter said from the front.

Chantey called Parkview Noble’s ER to let them know we were close and give an update on the patient’s condition. “OK,” she said. “They know we’re comin’.”

About eight minutes later, the highly coordinated partners had the patient in a room and gave report to the ER staff. As they brought the gurney back out to the nurses’ station, I heard Chantey noticeably exhale for the first time in 30 minutes. A Security officer brought them new sheets and wipes. They visited briefly as they sprayed everything down thoroughly and changed the covers.

We went back out to the van and they started taking stock of their space. Everything that was opened, discarded onto the ground, used, absorbed, had to be disposed of or put back in its home. The tidy corridor with its baskets and slots and sliding doors was once again ready. Everything was reset. Ready to go at a moment’s notice.

After a quick inventory, we stopped over at the Kendallville station to restock supplies. Both Medic 51 and 54 were in the garage but the quarters were quiet.

Only after we got back in the ambulance did I fully recognize the rush. There is an undeniable high that comes with the responsibility of life saving. I could see how making the right calls, altering someone’s life, could become addicting. How it could be a stimulant that brings you back again and again.

We stopped to get diesel fuel and pulled into Cromwell at exactly 5 a.m. From tones to return, the entire run had taken almost exactly two hours, but it felt like both an eternity and a blink.

Chantey immediately began charting.

6 a.m.

I had been awake for 23 hours. I’d made it. Between the conversation, anticipation, caffeine and adrenaline, I didn’t really feel that tired.

Now in my own car, I retraced the sharp curves I’d seen a handful of times that night. As the road rose underneath me, the fog seemed to be contained in ravines and lower land, making it tough to decipher between the haze and the trees. Slowly, as I got closer to home, the fog dissipated and day seemed to drop down slowly from above, until a chain of neon-fringed clouds announced that dawn had arrived.